Category: Critical Care

Keywords: ARDS (PubMed Search)

Posted: 6/16/2025 by Jordan Parker, MD

(Updated: 6/17/2025)

Click here to contact Jordan Parker, MD

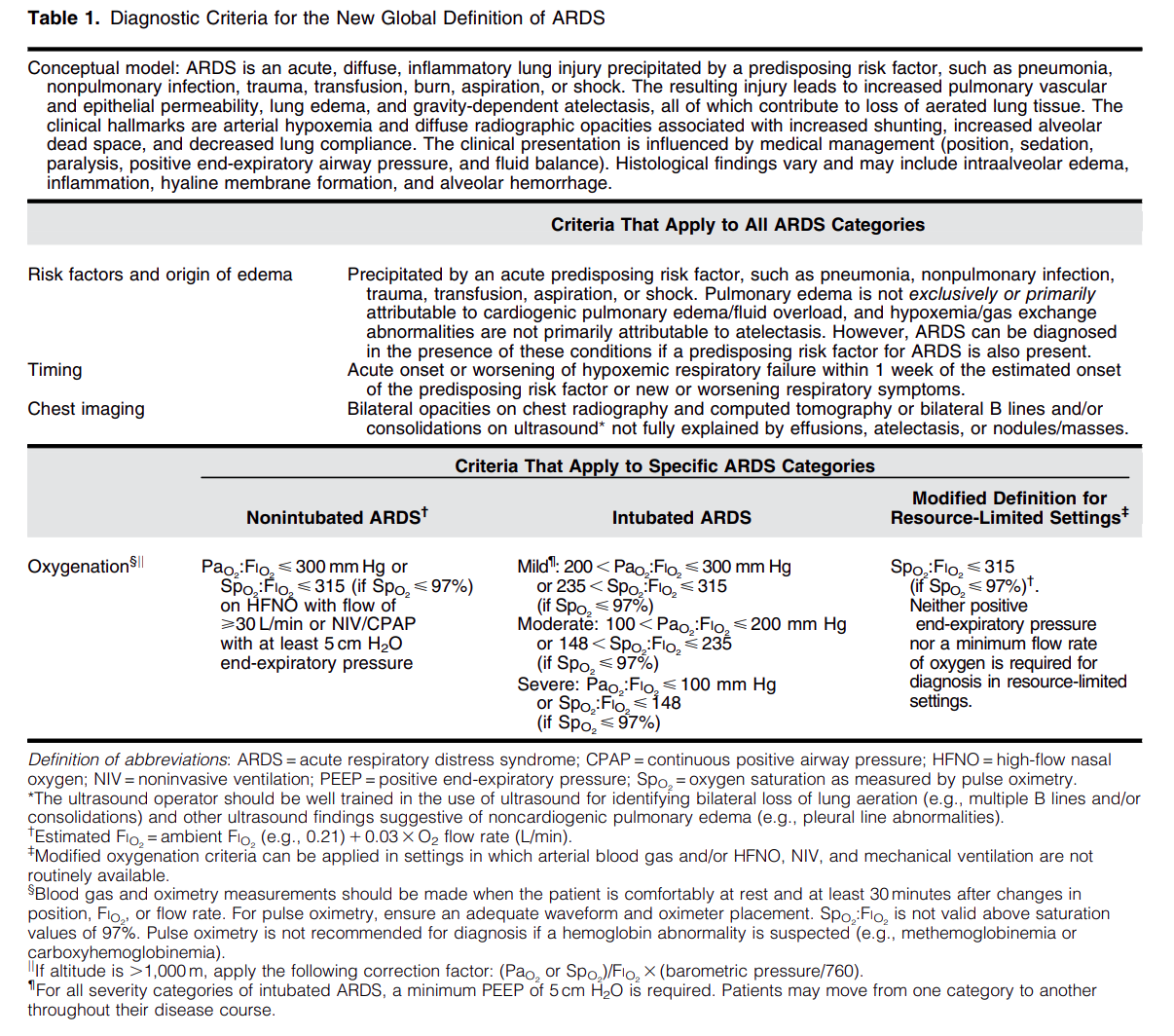

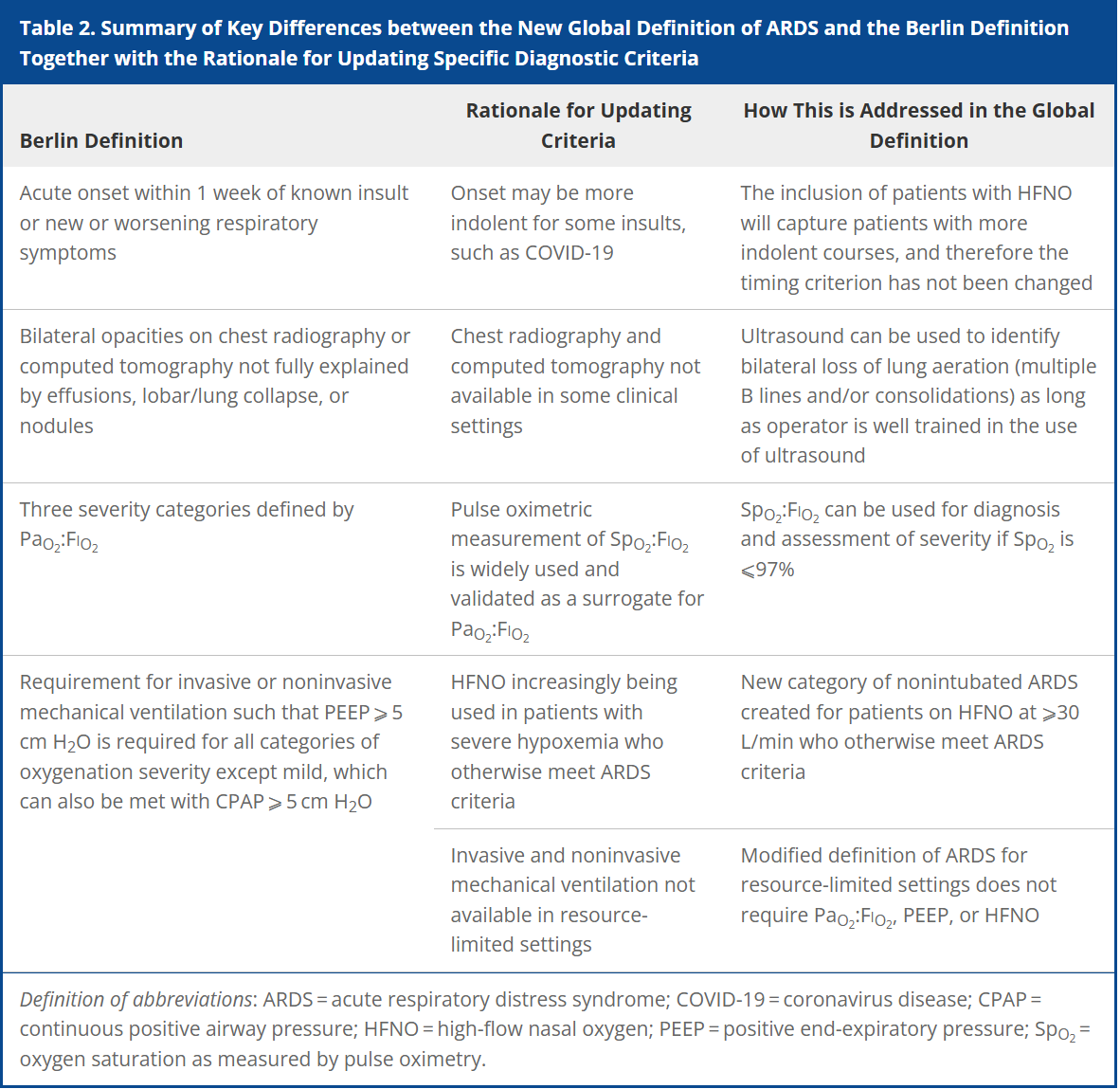

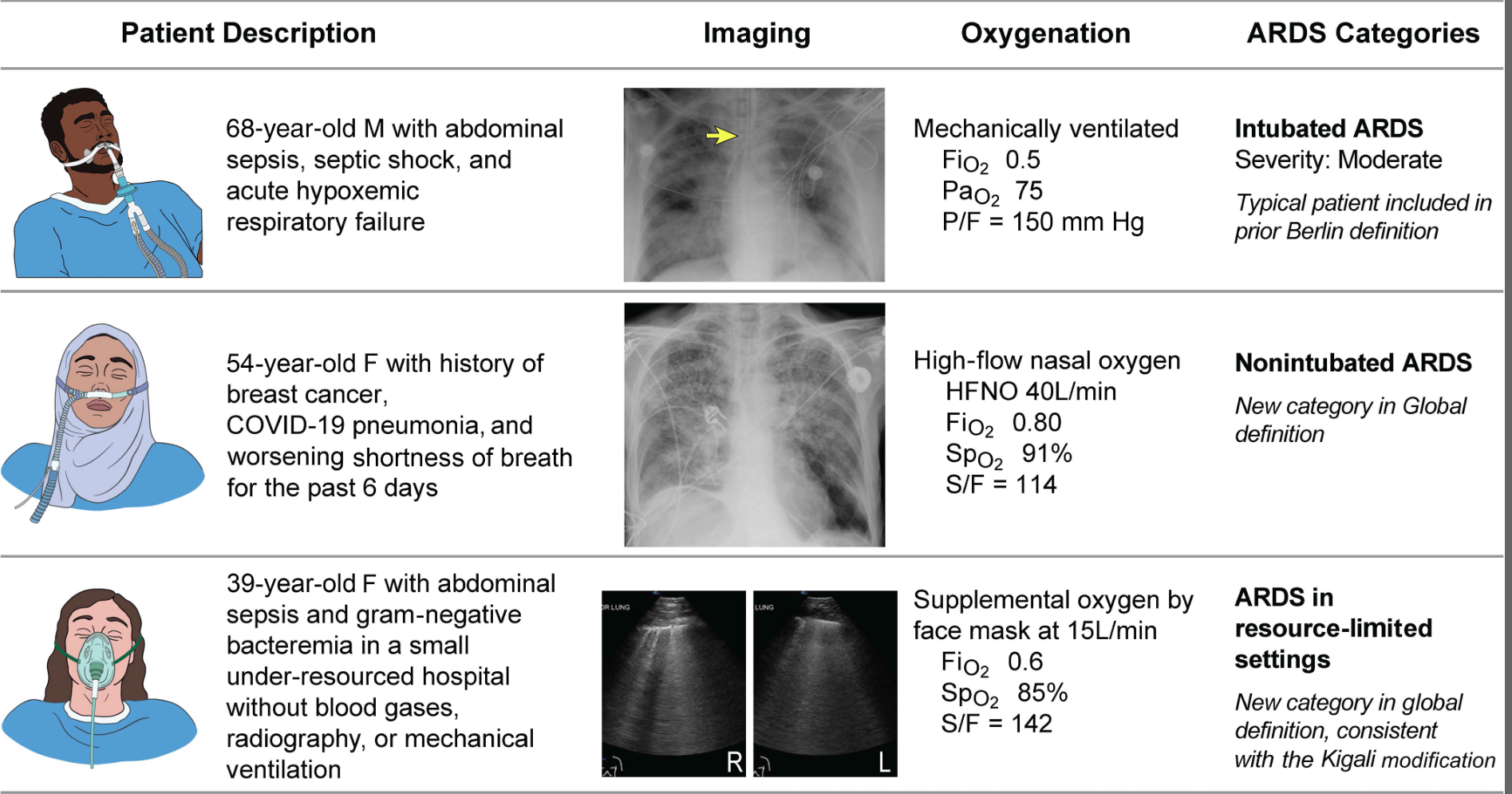

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is an acute, inflammatory lung injury that effects the lung diffusely and can be triggered by various insults. Aside from the Kigali modification, the most recent updated definition of ARDS was the Berlin definition in 2012. There have been many advances and changes in the understanding and clinical practice for managing patients with ARDS since then. In 2024, Matthay, et al. proposed the new global definition to build upon the Berlin criteria [1]. They addressed several important issues with the Berlin definition to improve the diagnostic criteria and improve ability for diagnosis in resource-limited settings.

ARDS Berlin Definition

Important updates for the Global definition of ARDS

Diagnostic Criteria for the New Global Definition of ARDS from Matthay et al.

The Global Definition of ARDS expands upon the Berlin definition. It was shown that this new definition improves diagnosis in resource-limited settings, allows for earlier detection, and better classification [2]. A retrospective study evaluating this new global definition found that there was a significant number of patients identified using this new definition who would have been missed using the Berlin definition [3]. These patients may benefit from ARDS directed therapies and further prospective studies will be needed to assess how this new definition effects clinical management of these patients using the new definition.

Helpful table/figure from the paper.

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 3/22/2025 by Jordan Parker, MD

(Updated: 4/15/2025)

Click here to contact Jordan Parker, MD

Background:

Acetaminophen can reduce hemoprotein induced oxidative damage. There has been growing discussion about its benefits in critically ill patients with sepsis. Multiple observational studies have found conflicting results on mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis. The ASTER trial found no difference in number of days alive and free of organ support. Interestingly their secondary outcomes found significantly less development of ARDS in the acetaminophen group 2.2% vs 8.5%, p = .01. There was also a non-statistically significant difference in mortality between the groups in favor of the acetaminophen group, 17% vs 22% p = 0.19. This study looked to further evaluate if acetaminophen used in critically ill patients with sepsis would have a decrease in mortality and increase in ventilator free days.

Study:

- Retrospective analysis of the Ibuprofen in Sepsis Study (ISS)

- The ISS was a randomized clinical trial comparing ibuprofen with placebo in critically ill patients with sepsis. Careful documentation of Acetaminophen use was recorded for the trial

- Critically-ill adults across 7 ICU’s in the US and Canada with known or suspected infection and severe organ dysfunction

- Acetaminophen use within 48 hours of enrollment = Acetaminophen exposed

- Primary outcome: 30-day mortality

- Secondary outcome: Renal failure and ventilator free days up to day 28

- 455 patients. 172 Acetaminophen unexposed, 235 Acetaminophen exposed.

Results:

- Propensity-matched analysis showed a lower mortality risk at 30 days in patients exposed to acetaminophen compared to unexposed, 32% vs 49% (HR 0.58, p .004)

- Secondary outcomes found acetaminophen exposed group had more ventilator free days (p .02) but there was no difference in renal failure among the groups.

Limitations:

- Major risk for confounding variables

- Retrospective and the data used was from decades ago (1989 -1995). Sepsis care has evolved and improved since this time

- Dose and frequency of acetaminophen administration was not standardized

Take Home Points:

- Interesting research that provides further support on the possible benefit to using acetaminophen in the management of critically ill patients with sepsis.

- With the ASTER trial showing a signal for the decrease in development of ARDS and this study showing improvement in mortality one could make a case for starting acetaminophen early in the course for these patients. However, the data is conflicting and more prospective, RCT’s are needed to confirm these findings before making this a staple for sepsis care in critically ill patients.

Obeidalla, S. N., Bernard, G. R., Ware, L. B., & Kerchberger, V. E. Acetaminophen and Clinical Outcomes in Sepsis: A Retrospective Propensity Score Analysis of the Ibuprofen in Sepsis Study. CHEST Critical Care. 2025;3(1):100-118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chstcc.2024.100118

Ware LB, Files DC, Fowler A, et al. Acetaminophen for Prevention and Treatment of Organ Dysfunction in Critically Ill Patients With Sepsis: The ASTER Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2024;332(5):390–400. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.8772

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 2/11/2025 by Jordan Parker, MD

Click here to contact Jordan Parker, MD

Background

Diagnosed by continuous seizure activity that lasts for 5 minutes or more and/or multiple seizures that occur without returning to baseline in-between each. Further classified as being convulsive or non-convulsive. Refractory status epilepticus can be defined as status epilepticus that does not respond to an adequately dosed benzodiazepine and another anti-seizure medication. The primary objective in management is to stop both clinical and electrographic seizures which can become an important point for those patients who require intubation and receive neuromuscular blockade. Essential to evaluate early for reversible causes (electrolytes, liver function, glucose, ammonia, medications) and for other precipitating causes with toxicology screening and CT head imaging with consideration for angiography and venography.

Management:

First-Line/Initial Therapy:

Lorazepam IV 0.1 mg/kg up to 4 mg per dose is the preferred agent, can be repeated after 5 minutes if seizures persist

Diazepam 0.15 mg/kg IV/0.2 mg/kg PR up to 10 mg, or midazolam IM 0.2 mg/kg up to 10 mg are also alternatives

Second-line/Urgent control: (Provided to all patients with SE after initial therapy)

- Levetiracetam 60 mg/kg, Valproate 40 mg/kg, and fosphenytoin 20 mgPE/kg were studied by Kapur et al., and they found similar rates of resolution of status epilepticus with similar rates of adverse events.

- Phenobarbital 15-20 mg/kg is another agent that has good efficacy and is remerging as an effective agent. Can cause respiratory depression at high doses.

- Keppra may have the best side-effect profile to consider.

- Valproate can cause hepatotoxicity, elevated ammonia and thrombocytopenia.

- Fosphenytoin can cause hypotension and arrhythmias.

Third-line:

Midazolam 0.2 mg/kg load followed by 0.05 – 2 mg/kg/hr infusion

Propofol 1-2 mg/kg load followed by 20-200 mcg/kg/min infusion

Ketamine 0.5 – 3 mg/kg load followed by 1.5-10 mg/kg/hr infusion

Pentobarbital 5 mg/kg load followed by 0.5-5 mg/kg/hr infusion

- Propofol carries the risk of propofol infusion syndrome with high doses or prolonged infusions, some favor midazolam because of this.

No conclusive data to support one over another.

Important Considerations

- A common mistake is to under-dose benzodiazepines for initial therapy, give the full weight-based dose as described above.

- Following initial management it is important to monitor patients with continuous EEG if they have not returned to their neurologic baseline

- Propofol, midazolam or ketamine are good options for induction for intubation.

- Consider against using etomidate for induction of intubation since it can cause myoclonus which can complicate the picture if you are already worried about seizures, can be hard to differentiate.

- If intubation is required and EEG is not readily available consider reversal of neuromuscular blockade after intubation to better monitor for continued seizures.

- If in refractory status epilepticus despite using a second-line agent and a third line agent then consider adding a second agent from the second-line/urgent control that was not previously started (fosphenytoin, valproate, levetiracetam, or phenobarbital).

Brophy GM, Bell R, Claassen J, Alldredge B, Bleck TP, Glauser T, Laroche SM, Riviello JJ Jr, Shutter L, Sperling MR, Treiman DM, Vespa PM; Neurocritical Care Society Status Epilepticus Guideline Writing Committee. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of status epilepticus. Neurocrit Care. 2012 Aug;17(1):3-23. doi: 10.1007/s12028-012-9695-z. PMID: 22528274.

Jennifer V Gettings, Fatemeh Mohammad Alizadeh Chafjiri, Archana A Patel, Simon Shorvon, Howard P Goodkin, Tobias Loddenkemper. Diagnosis and management of status epilepticus: improving the status quo. The Lancet Neurology. 2025;24(1):65-76.

Kapur J, Elm J, Chamberlain JM, Barsan W, Cloyd J, Lowenstein D, Shinnar S, Conwit R, Meinzer C, Cock H, Fountain N, Connor JT, Silbergleit R; NETT and PECARN Investigators. Randomized Trial of Three Anticonvulsant Medications for Status Epilepticus. NEJM. 2019 Nov 28;381(22):2103-2113. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1905795.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Subclavian CVC (PubMed Search)

Posted: 12/2/2024 by Jordan Parker, MD

(Updated: 12/3/2024)

Click here to contact Jordan Parker, MD

Background:

Ultrasound-guided subclavian central venous catheter (CVC) placement has become a preferred site due to low risk of infection and a low risk of complication. Complications include arterial puncture, pneumothorax, chylothorax, and malposition of the catheter. Ultrasound guidance can significantly reduce the risk of these complications aside from catheter malposition. The most common sites of malposition are in the ipsilateral internal jugular vein or the contralateral brachiocephalic vein. This study sought to evaluate the rate of catheter malposition between left-and right-sided subclavian vein catheter placement using ultrasound guidance with an infraclavicular approach.

Study:

Results:

Take Home:

For infraclavicular ultrasound-guided subclavian CVC placement, consider using the left-side over the right if no contraindications for left-sided access exist.

The authors proposed anatomical differences in the subclavian veins as the etiology for the difference in malposition rates. Images are provided in the paper. Patient positioning may also play a role which the authors commented on and other clinicians have responded to the article with their thoughts.

Supraclavicular subclavian vein access is also discussed as an alternative option that can provide real-time tracking of the guidewire into the correct location to reduce malposition rates.

Read More below.

Supraclavicular approach and response to the article:

Kander, Thomas MD, PhD1,2; Adrian, Maria MD, PhD1,3; Borgquist, Ola MD, PhD1,3. Right Subclavian Venous Catheterization: Don’t Throw the Baby Out With the Bathwater. Critical Care Medicine 52(12):p e645-e646, December 2024. | DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000006388

Adrian M, Kander T, Lundén R, Borgquist O. The right supraclavicular fossa ultrasound view for correct catheter tip positioning in right subclavian vein catheterisation: a prospective observational study. Anaesthesia. 2022 Jan;77(1):66-72. doi: 10.1111/anae.15534. Epub 2021 Jul 14. PMID: 34260061.

Patient position discussion:

Tokumine, Joho MD, PhD; Moriyama, Kiyoshi MD, PhD; Yorozu, Tomoko MD, PhD. Influence of Arm Abduction on Ipsilateral Internal Jugular Vein Misplacement During Ultrasound-Guided Subclavian Venous Catheterization. Critical Care Medicine 52(12):p e646-e647, December 2024. | DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000006410

Shin KW, Park S, Jo WY, Choi S, Kim YJ, Park HP, Oh H. Comparison of Catheter Malposition Between Left and Right Ultrasound-Guided Infraclavicular Subclavian Venous Catheterizations: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Critical Care Medicine. 2024 Oct 1;52(10):1557-1566. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000006368. Epub 2024 Jun 24. PMID: 38912886.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Septic Shock, Vitamin B12, Hydroxocobalamin, sepsis (PubMed Search)

Posted: 10/8/2024 by Jordan Parker, MD

Click here to contact Jordan Parker, MD

Background:

Septic shock is a severe and common critical illness that is managed in the emergency department. Our current foundation of treatment includes IV fluids, empiric antibiotic coverage, vasopressor therapy, source control and corticosteroids for refractory shock. The levels of nitric oxide (NO) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) are elevated in sepsis and associated with worse outcomes. Hydroxocobalamin is an inhibitor of NO activity and production and a scavenger of H2S [1,2]. Most of the current data is limited to observational studies looking at hydroxocobalamin in cardiac surgery related vasodilatory shock with few case series and reports for use in septic shock. The available data has shown an improvement in hemodynamics and reduction in vasopressor requirements in various vasodilatory shock states [2]. Chromaturia and self-limited red skin discoloration are common side effects but current data has not shown significant adverse events [3,4]. Patel et al, performed a phase 2 single-center trial to evaluate use of high dose IV hydroxocobalamin in patients with septic shock.

Study:

Results

Take home

There is a low risk of serious adverse events from high dose hydroxocobalamin use [3,4]. For now, it may be reasonable to consider in cases of septic shock refractory to standard care but there isn’t enough data to support its regular use yet.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: DKA (PubMed Search)

Posted: 8/13/2024 by Jordan Parker, MD

Click here to contact Jordan Parker, MD

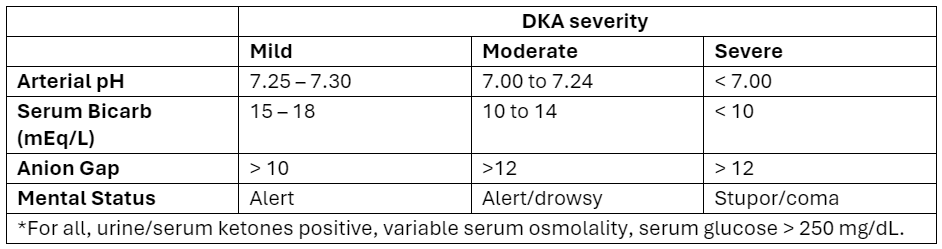

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a serious condition that carries the risk of significant morbidity and mortality if not managed appropriately. Typically managed with an infusion of regular insulin, IV fluids, and electrolytes, there is evidence to support treatment of mild to moderate DKA with a subcutaneous (SQ) regimen using a combo of fast-acting and long-acting insulin instead, decreasing the need for ICU admission without increasing adverse events [1].

What patients?

Adapted from Abbas et al.

How to manage?

Initial dose

Subsequent dosing:

If serum glucose is > 250 mg/dL

If serum glucose is < 250 mg/dL

Bottom Line

DKA management with a SQ insulin protocol is a reasonable approach for patients with mild to moderate DKA, is supported by the American Diabetes Association [5], and can be particularly helpful in this era of ED boarding and bed shortages. Give a long-acting insulin dose every 24 hours (or restart the patient’s home long-acting regimen) and short-acting insulin every 2 to 4 hours. Aggressive IV fluid resuscitation, electrolyte repletion, and treatment of underlying precipitating cause remain additional cornerstones of DKA management.