Category: Critical Care

Keywords: OCHA, VF, ventricular fibrillation, cardiac arrest, shockable, Occult VF (PubMed Search)

Posted: 1/28/2026 by Kami Windsor, MD

(Updated: 2/1/2026)

Click here to contact Kami Windsor, MD

A crucial part of cardiac arrest management is identification of the underlying rhythm, with key aspects of management diverging depending whether shockable (pulseless ventricular tachycardia/pVT or ventricular fibrillation/VF) or unshockable (pulseless electrical activity/PEA or asystole).

A recent study prospectively evaluated adult atraumatic out-of-hospital-cardiac-arrests (OHCAs) presenting to the ED, to determine what percentage of cases had “Occult VF” – VF found point-of-care echocardiogram but not by ECG. The researchers only included cases with simultaneous ECG and echo assessments for the initial 3 pulse checks. Echo and ECG determinations for the study were adjudicated by research team members.

They found that:

Major limitations:

Bottom Line: Point-of-care echocardiogram continues to have value in the management of cardiac arrest, potentially changing management and affecting post-ROSC decisions. Ensuring high-quality CPR, with appropriate defibrillation and anti-arrhythmic strategies, remains paramount in management of shockable OHCA.

Gaspari R, Adhikari S, Gleeson T, et al. Occult Ventricular Fibrillation Visualized by Echocardiogram During Cardiac Arrest: A Retrospective Observational Study From the Real-Time Evaluation and Assessment for Sonography-Outcomes Network (REASON). J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2025;6(1):100028. doi: 10.1016/j.acepjo.2024.100028.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: sepsis, subtypes, long term mortality, disability (PubMed Search)

Posted: 1/20/2026 by Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

Click here to contact Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

Settings: Secondary analysis of the Crystalloid Liberal or Vasopressors Early Resuscitation in Sepsis (CLOVERS) trial.

Participants:

1368 patients who survived on day 28 after enrollment, and were retrospectively assigned different subtypes:

Low risk, barriers to care. Younger patients with few comorbidities, less severe disease,

Unhealthy baseline with severe illness: Previously healthy with severe illness and complex needs after discharge, barriers to care.

Multimorbidity. Older patients with more comorbidities and are frequently readmitted.

Low functional status: Poor functional status. Older patients with high prevalence of frailty at discharge and high functional needs who are often discharged to a facility.

Unhealthy baseline with severe illness: Existing poor health with severe illness and complex needs after discharge. Older patients with severe comorbidities, more severe illness, high functional needs, prolonged hospital stay,

Outcome measurement:

A) 90-day mortality,

B) 6-month and 12-month EuroQol 5D five level score

Study Results:

A) 90-day mortality:

Unhealthy baseline with severe illness (37.6%) > low functional status (45.5%) > multimorbidity (17.4%) > unhealthy baseline, severe illness (13.2%) > Low risk (5.1%).

B) 6-month EuroQol 5D-Five Level: lower score, lower functional outcomes)

Unhealthy baseline with severe illness (0.53) > unhealthy baseline, severe illness (0.68) > low functional status (0.69) > multimorbidity (0.78) > Low risk (0.80).

Discussion:

a) The framework, readily available to clinicians provides good prognostic tools for mortality.

b) Although there was prediction of poor functional outcomes at 6-month and 12-month, the differences between subtypes in their EuroQoL 5D-5L did not seem to correspond to 90-day mortality. Low functional status group had 2nd-highest rate of mortality, but only 3rd in their EuroQoL 5D-3L score. Thus, there needs to be more studies in these nuances.

Conclusion:

Sepsis survivor subtypes—assigned using only three routinely available discharge variables—are strongly associated with 3-month mortality and long-term disability and HRQOL up to 12 months

Flick RJ, Kamphuis LA, Valley TS, Armstrong-Hough M, Iwashyna TJ. Association of Sepsis Survivor Subtypes With Long-Term Mortality and Disability After Discharge: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Crit Care Med. 2026 Jan 1;54(1):45-54. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000006933. Epub 2025 Nov 13. PMID: 41231072.

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 1/13/2026 by Caleb Chan, MD

Click here to contact Caleb Chan, MD

Recall that MAP = (cardiac output) x (systemic vascular resistance)

Consequently, a patient can be normotensive due to increased SVR despite a very low cardiac output and shock. In fact, normotensive shock may have worse outcomes compared to patients with isolated hypotension.

Take home points:

Yerasi C, Case BC, Pahuja M, et al. "The Need for Additional Phenotyping When Defining Cardiogenic Shock." JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15(8):890-895.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: alcohol withdrawal syndrome, AWS, phenobarbital (PubMed Search)

Posted: 1/6/2026 by William Teeter, MD

Click here to contact William Teeter, MD

Yet another study (this time ED focused) has shown benefits to patients and hospital systems when implementing a Phenobarbital-based treatment algorithm. Shorter ED LOS, fewer admissions, and treatment with phenobarbital alone was independently associated with discharge when compared to mixed treatment regimens. Higher age and heart rate, as well as treatment with benzodiazepines alone were independently associated with hospitalization.

Cautions/contraindications include: pregnancy, cirrhosis with history of hepatic encephalopathy (consider dose reduction in hepatic dysfunction), acute intermittent porphyria, and prior chronic phenobarbital use.

Phenobarbital has a long half life (one of its benefits in AWS) and works synergistically with benzodiazepines, so should be used preferentially as monotherapy in patients where the diagnosis is relatively certain and who have not received high doses of benzos. Once the diagnosis is made, go with phenobarbital and stick with it.

PulmCrit has an excellent in-depth article on this and also see Dr. Flint's pearl describing another centers experience in a hospital-wide rollout (links below).

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Intubation, RSI, norepinephrine, hypotension, vasopressors (PubMed Search)

Posted: 12/29/2025 by Mark Sutherland, MD

(Updated: 12/30/2025)

Click here to contact Mark Sutherland, MD

Perintubation hypotension is a major problem, and can precipitate hemodynamic collapse and cardiac arrest for a multitude of reasons. To prevent this, many different strategies have been explored (some of which work and some of which don't), including empiric IV fluid boluses, additional resuscitation before intubation, switching or dose-reducing induction agents and much more. But we know pressors like norepinephrine raise blood pressure effectively, so should we just put everybody on a norepinephrine drip before we intubate them?

Probably not. The EPITUBE trial included 210 patients at a single-institution undergoing cardiac surgery, and randomized them to empirically starting a norepinephrine infusion before induction vs just rescue ephedrine when needed (fairly standard anesthesia practice). For the empiric norepinephrine group, they started at 0.06 ug/kg/min, and once the drip was up and running, they titrated for a MAP of 65-80 (which could include stopping the norepi if that the patient remained above 80 despite downtitration)

The incidence of severe hypotension (MAP < 55) did not differ between the groups, although fewer empiric norepinephrine patients had a MAP < 65 at any point (which was a secondary outcome). Naturally, the differences between this practice setting (the cardiac surgery OR) and the emergency department should be noted and are not addressed by this study.

Bottom line: There isn't good evidence to support empirically starting all patients on a norepinephrine infusion prior to intubation as a method to prevent perintubation hypotension. You should always have rapid access to vasopressors when intubating, and should continue to tailor your therapy to the individual patient, but probably don't start just putting everyone on norepinephrine before you intubate them.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: ventilator, extubation, critical care, respiratory, SBT (PubMed Search)

Posted: 12/22/2025 by Zachary Wynne, MD

(Updated: 12/23/2025)

Click here to contact Zachary Wynne, MD

The emergency department serves many critically ill patients that require airway management and mechanical ventilation. Most of these patients go on to require ICU care. However, some patients require only brief intubation and should be appropriate candidates considered for emergency physician-driven extubation. Early extubation can minimize the risks associated with mechanical ventilation for patients such as ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP), ventilator induced lung injury (VILI), and others. Additionally, in setting of high levels of ED boarding and limited ICU resources, extubating appropriate candidates in the ED can reduce boarding times and improve patient flow.

Who?

Screening Checklist

Testing

Prepare - depending on institution, may require consultation with the hospital intensivist

Perform - see this video courtesy of Respiratory Skills - LSC on performing extubation

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 12/16/2025 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

(Updated: 2/1/2026)

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Pitfalls in Lactate Interpretation

Levy B, et al. Lactate dynamics as a marker of perfusion: physiological interpretation and pitfalls. Intensive Care Med. 2025; 51:2145-8.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: septic shock, capillary refill time, personalized medicine, fluids, vasopressors, resuscitation (PubMed Search)

Posted: 12/9/2025 by Jessica Downing, MD

Click here to contact Jessica Downing, MD

Last month, Mark Sutherland posted an overview of a new article investigating the use of personalized MAP targets in resuscitation for septic shock (1). Now, the authors of ANDROMEDA-SHOCK-2 (2) suggest a new multimodal approach to personalize resuscitation in septic shock that largely operates outside of the traditional focus on MAP and lactate.

In 2019, the ANDROMEDA-SHOCK Trial (3) suggested that capillary refill time (CRT) may be a better resuscitation in septic shock than lactate. Now, the same group is suggesting that a stepwise algorithm to guide resuscitation may provide more optimal and “personalized” results when compared to usual care for patients with abnormal CRT:

Tier 1: If CRT is abnormal, assess pulse pressure (PP) and DBP:

Tier 2: If CRT remains abnormal despite the above, use POCUS to assess for cardiac dysfunction.

The authors found that at 6 hours, following the protocol resulted in increased use of dobutamine, lower fluid balance, and similar CVP and MAP with lower lactate levels and CRT. They reported an improvement in their composite hierarchical outcome at 28 days, primarily driven by a shorter duration of organ support (vasoactives, mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy) and among sicker patients. No difference in mortality was observed between groups.

Food for Thought:

Study Details:

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Shock, procedures, arterial line, blood pressure, mean arterial pressure, MAP (PubMed Search)

Posted: 12/2/2025 by Kami Windsor, MD

Click here to contact Kami Windsor, MD

We have all been there – an ED patient with circulatory shock requiring vasoactive medications and, therefore, an arterial line for accurate and close monitoring of the MAP and appropriate titration of the infusions. But does it save lives?

The recently published NEJM article by Muller et al. takes a look at noninvasive BP monitoring (NIBP) by cuff versus early arterial catheterization in patients with hypotension and evidence of tissue hypoperfusion:

Bottom Line: This trial indicates that in appropriately-selected patients with shock, such as those not on high doses of vasopressors, with BMI < 40 and an ability to consistently obtain NIBP measurements, early arterial line placement in the ED for vasopressor titration is unlikely to improve outcomes. It is important to note other potential indications for arterial line placement (severe hypoxia, inability to obtain reliable SpO2 with need for ABG monitoring, cardiac arrest, pain related to NIBP cuff monitoring, intracranial hemorrhage, etcetera) may still make arterial line placement in the ED prudent and better for overall patient care.

*France refers to norepi by the tartrate formulation dose, US refers to the base norepi dose (ratio is 2:1 tartrate: base).

Muller G, Contou D, Ehrmann S, et al.; CRICS-TRIGGERSEP F-CRIN Network and the EVERDAC Trial Group. Deferring Arterial Catheterization in Critically Ill Patients with Shock. N Engl J Med. 2025;393(19):1875-1888. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2502136.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: critically ill, ED, boarding, outcome (PubMed Search)

Posted: 11/25/2025 by Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

Click here to contact Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

Settings: this is a meta-analysis of 17 observational studies about boarding of critically ill patients in US Emergency Departments. All studies were from urban, academic centers.

Participants:

Outcome measurement: all cause mortality, as reported by the authors of the original studies.

Study Results:

Discussion:

Conclusion:

Critically ill patients boarding in the U.S. Emergency Departments were associated with a non-statistically signi?cant increase in odds of mortality and hospital length of stay compared to non-boarded patients

Htet NN, Walker JA, Jafari D, Rech MA, Hintze T, Moran M, Bai J, Dinh K, Essaihi A, Wilairat S, Huddleson B, Tran QK. Outcomes of boarding critically ill patients in U.S. EDs: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2025 Oct 17;99:339-347. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2025.10.036. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 41151219.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: bicarbonate, metabolic acidosis, renal replacement therapy, acute kidney injury (PubMed Search)

Posted: 11/25/2025 by Jessica Downing, MD

Click here to contact Jessica Downing, MD

The role of sodium bicarbonate in the treatment of severe acidemia has been controversial, with some studies suggesting no benefit, and others indicating that it may help reduce need for renal replacement therapy (RRT) and even improve mortality. The BICARICU-2 Trial was an open-label multicenter RCT conducted in France that evaluated the impact of a bicarb infusion among patients with metabolic acidosis and moderate to severe AKI.

There was no difference in 90 day mortality, but patients in the bicarb group were less likely to be started on RRT (38% vs 47% in the control group) using pre-defined criteria for RRT initiation, and had a 50% lower rate of bloodstream infections. Patients in the bicarb group who were started on RRT met criteria for RRT later than those in the control group (median 31h vs 15.5h).

Study Details:

Patient Population:

Intervention:

RRT Triggers:

Jung B, Jabaudon M, De Jong A, Bitker L, Audard J, Klouche K, Sarton B, Guitton C, Lasocki S, Rieu B, Canet E, Jeantrelle C, Roquilly A, Mayaux J, Verdonk F, Pottecher J, Ferrandiere M, Riu B, Garcon P, Assefi M, Detouche P, Forel JM, Roger C, Bourenne J, Jacquier S, Bougon D, Rolle A, Corne P, Benchabane N, Richard JC, Asehnoune K, Chanques G, Reignier J, Belafia F, Fosset M, Huguet H, Futier E, Molinari N, Jaber S; BICARICU-2 Study Group. Sodium Bicarbonate for Severe Metabolic Acidemia and Acute Kidney Injury: The BICARICU-2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2025 Oct 29:e2520231. doi: 10.1001/jama.2025.20231. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 41159812; PMCID: PMC12573113.

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 11/18/2025 by Caleb Chan, MD

Click here to contact Caleb Chan, MD

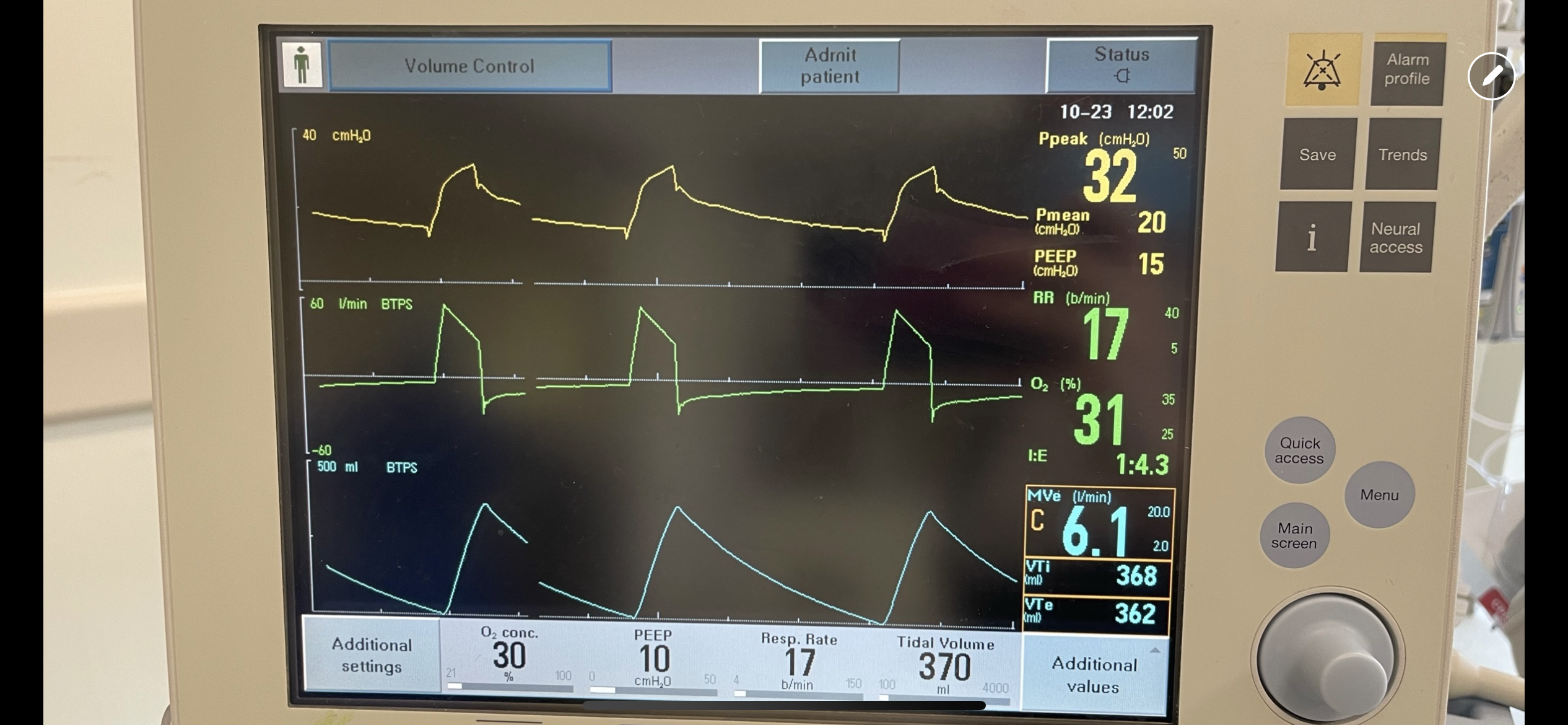

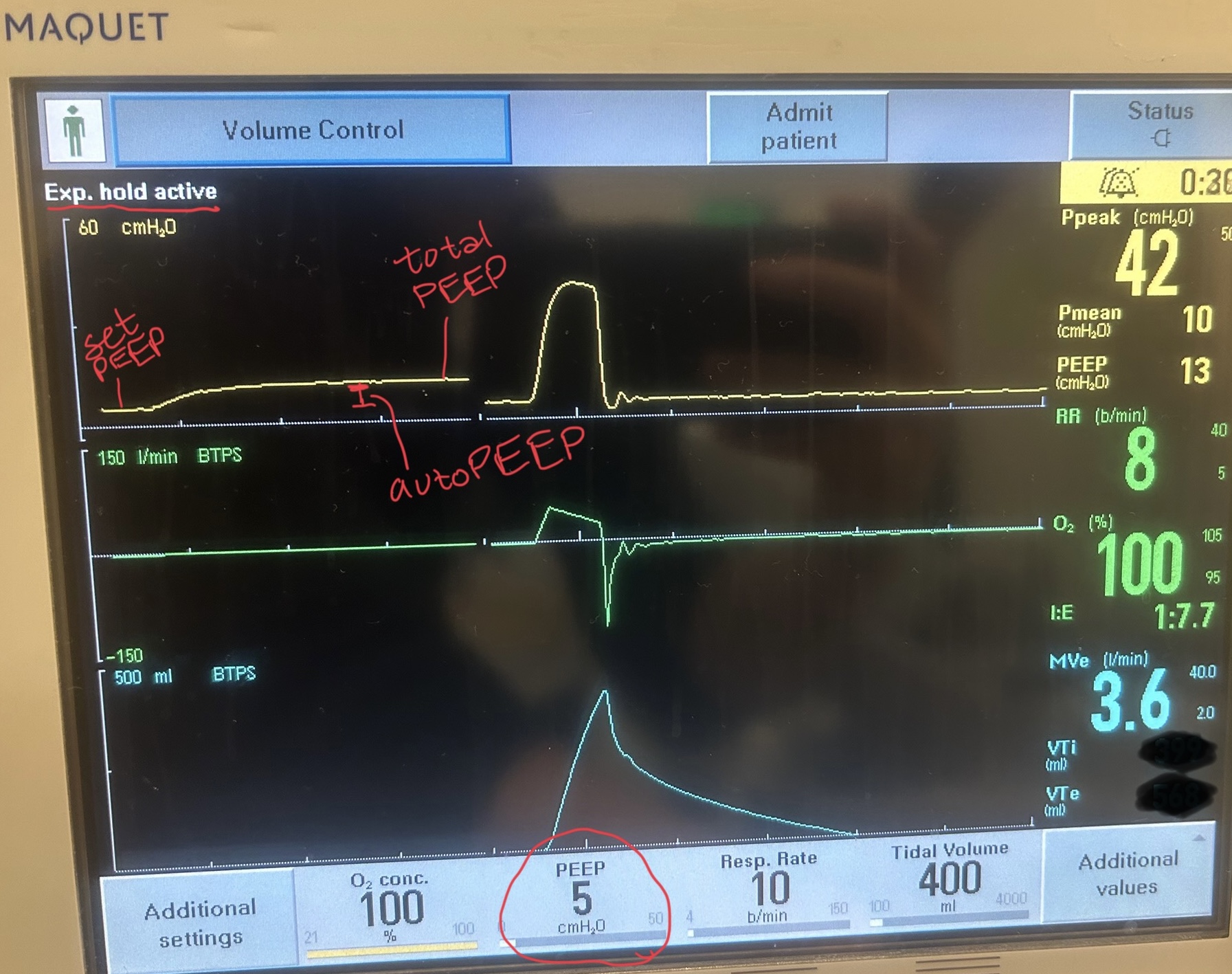

This is an actual patient case:

65 y/o pt intubated for hemoptysis and started on nebulized transexamic acid. Overnight, the pt is found to have severe breath stacking/auto-PEEPing and consequently is started on neuromuscular blockade. The pt has no history of asthma or COPD and the ETT is clear without obstruction.

Ventilator waveforms are as shown. What is the issue?

Explanation:

On expiration, the ventilator pressure (and the pressure curve waveform on the ventilator) should drop to the set PEEP (10 cm H2O in this case) immediately. This is true regardless of whether it is volume control, pressure control, PRVC etc. For this patient, the pressure curve is not dropping to the set PEEP immediately on expiration, rather, it slowly decays and does not even reach the set PEEP before the beginning of the next breath. This is not due to a patient issue, but rather an obstruction at the level of the ventilator. In particular, an obstruction in the expiratory limb of the tubing where flow returns to the ventilator from the patient. TXA is known to crystallize on the expiratory filter which can cause this type of obstruction if it is not changed frequently enough, preventing the pressure from dropping to PEEP and the patient from fully exhaling.

In this case, the obstruction was localized to the expiratory filter based on the ventilator waveforms and the filter was exchanged. The waveforms normalized, the patient had no obstruction or breath stacking, the neuromuscular blockade discontinued, and the patient was subsequently extubated without issue.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Critical Care, Surgical Critical Care, Fellowship, Training, Medical education, Emergency Medicine-Critical Care, EM-CC (PubMed Search)

Posted: 11/12/2025 by William Teeter, MD

Click here to contact William Teeter, MD

This study surveyed 111 emergency medicine (EM) trainees to identify factors influencing their choice of critical care (CC) fellowship pathways, particularly surgical critical care (SCC). Respondents included 42 fellows and 69 residents, with most pursuing anesthesiology or medicine CC; only 15 intended SCC.

Key determinants of pathway selection were:

Limited exposure to EM-SCC during residency was noted—only 28% had access to such fellowships, and 42% interacted with surgical intensivists, despite 41% envisioning SCC practice.

Intellectual appeal ranked highest for entering CC, above job prospects or lifestyle.

Fellowship components most valued were:

While descriptive, the authors noted many respondents cited the "preliminary surgical year" as a reason that the Surgical Critical Care pathway is less attractive.

The authors conclude that respondents pursued a career in CC for "intellectual appeal and desire for additional expertise" and that improving EM-SCC matriculation requires targeted interventions.

Hynes AM, Carver TW, Owodunni OP, et al. Attracting Emergency Medicine-Trained Residents to Surgical Critical Care: The Implications From a Nationwide Survey of Emergency Medicine Trainees Interested in Critical Care. Crit Care Med. 2025 Oct 31. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000006935.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Sepsis, Shock, Hypotension, Fluids, Ultrasound, Vasopressors (PubMed Search)

Posted: 11/4/2025 by Mark Sutherland, MD

Click here to contact Mark Sutherland, MD

Another month, another study of hemodynamic targets in sepsis… The age-old questions: is a MAP > 65 a good target for everybody, or should we individualize? Should we just give a bolus of fluids to everyone and then move to pressors, or should this strategy change patient to patient?

Huet et al have a preprint that'll appear in Intensive Care Medicine looking at this question in 517 patients. I can't reprint it here due to copyright (follow link below, go to full PDF and scroll to figures at bottom if curious), but basically their algorithm was 1) check if patient is fluid responsive via either echo or swan, 2) give fluid if yes, 3) do something else (pressors) if no.

Importantly the differences were not statistically significant, but they found a strong, nearly significant, trend towards benefit on SOFA score, ICU and hospital LOS in the “personalized therapy” group (also of note, these are dubious as patient oriented outcomes). The sickest patients (by SOFA) showed the most benefit.

Bottom Line: The “personalized hemodynamic therapy” literature continues to show a modest benefit of using tools like echo (e.g. LVOT VTI) to determine if the patient is fluid responsive (or fluid tolerant) and NOT give fluid (instead using pressors) if that is not the case, but for now there's relatively limited support for hyper-personalized approaches like varying MAP goals or otherwise mixing up your strategy. Some day we'll likely find a more nuanced approach, but for now I think a reasonable strategy in critically ill septic patients is to use ultrasound to determine if the patient needs fluid, if yes give fluid and reassess, and if not move to pressors, to maintain a MAP > 65.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Cardiac arrest, norepinephrine, re-arrest, advantage, epinephrine (PubMed Search)

Posted: 11/1/2025 by Robert Flint, MD

Click here to contact Robert Flint, MD

A scoping review of literature involving norepinephrine use during cardiac arrest associated with a shockable rhythm found:

-evidence in animal and signal in human trials of improved myocardial and cerebral blood flow

-a suggestion of less re-arrest

There is not enough evidence comparing epinephrine to norepinephrine however this would be an excellent area of research with a theoretical advantage to norepinephrine.

Bouman, S.J., Baldussu, E., Franssen, G.H. et al. The effects of norepinephrine in shockable cardiac arrest, a scoping review. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 33, 155 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-025-01480-6

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Ventilator, autoPEEP, asthma, COPD, obstructive lung disease (PubMed Search)

Posted: 10/28/2025 by Zachary Wynne, MD

Click here to contact Zachary Wynne, MD

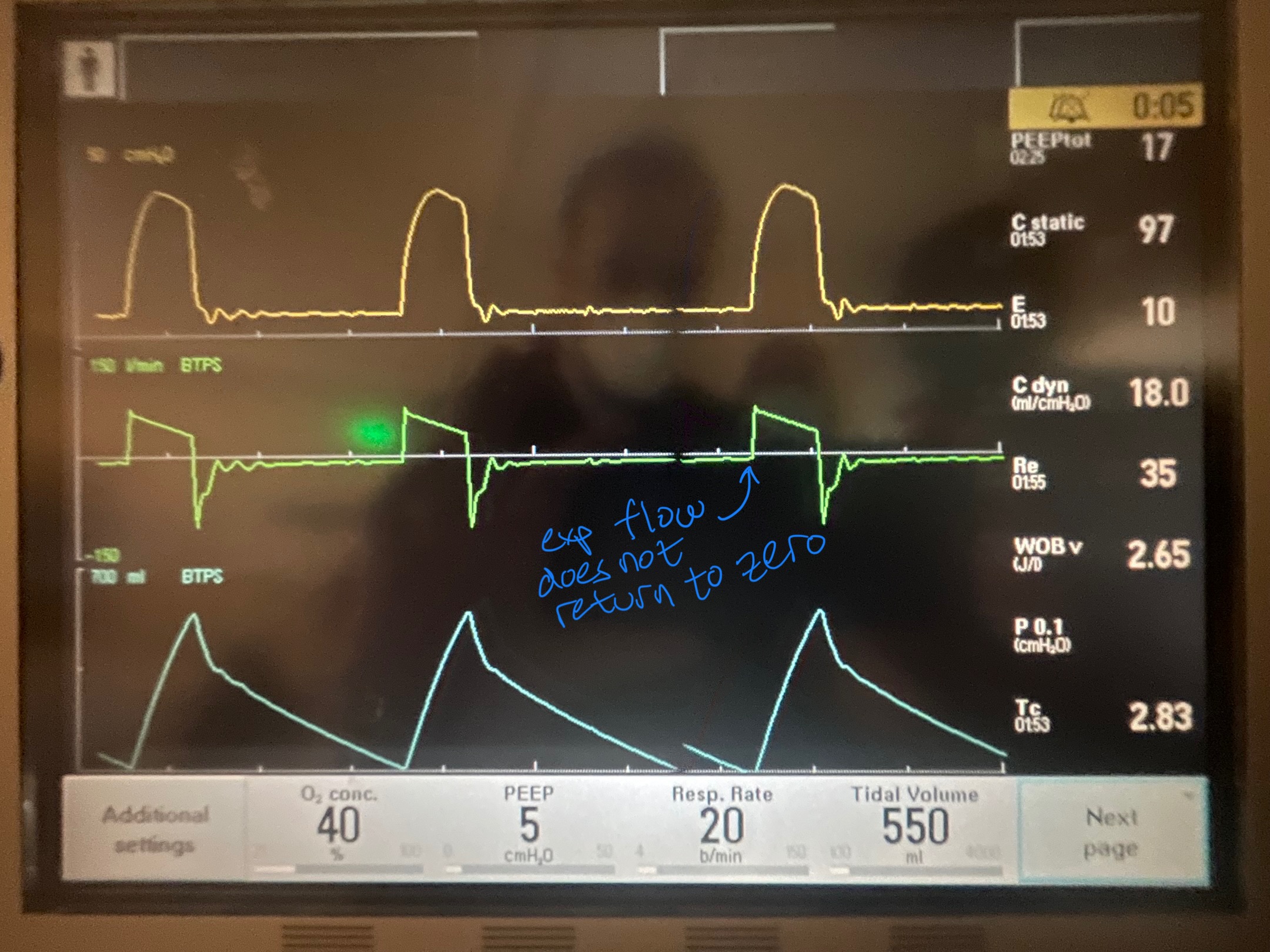

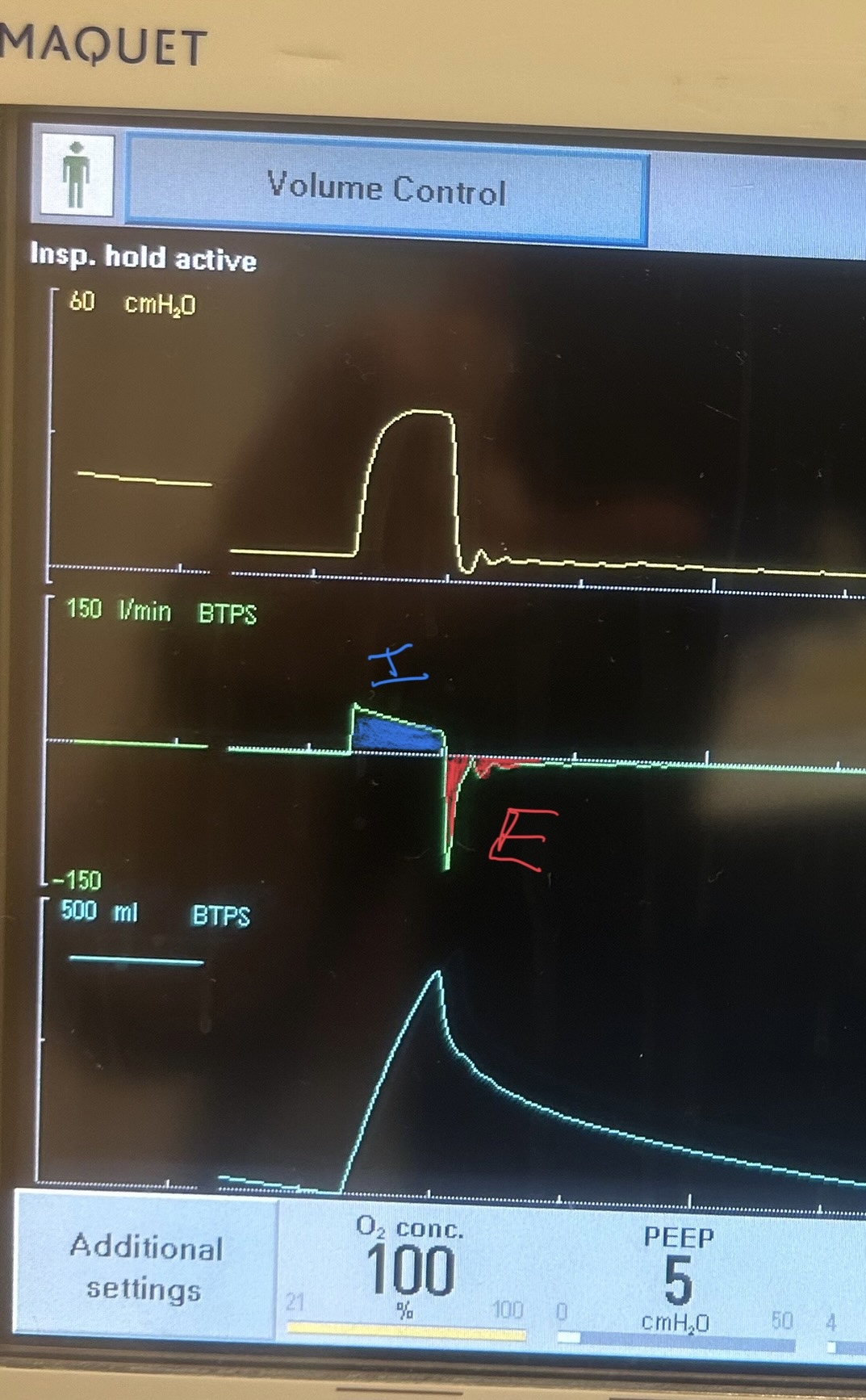

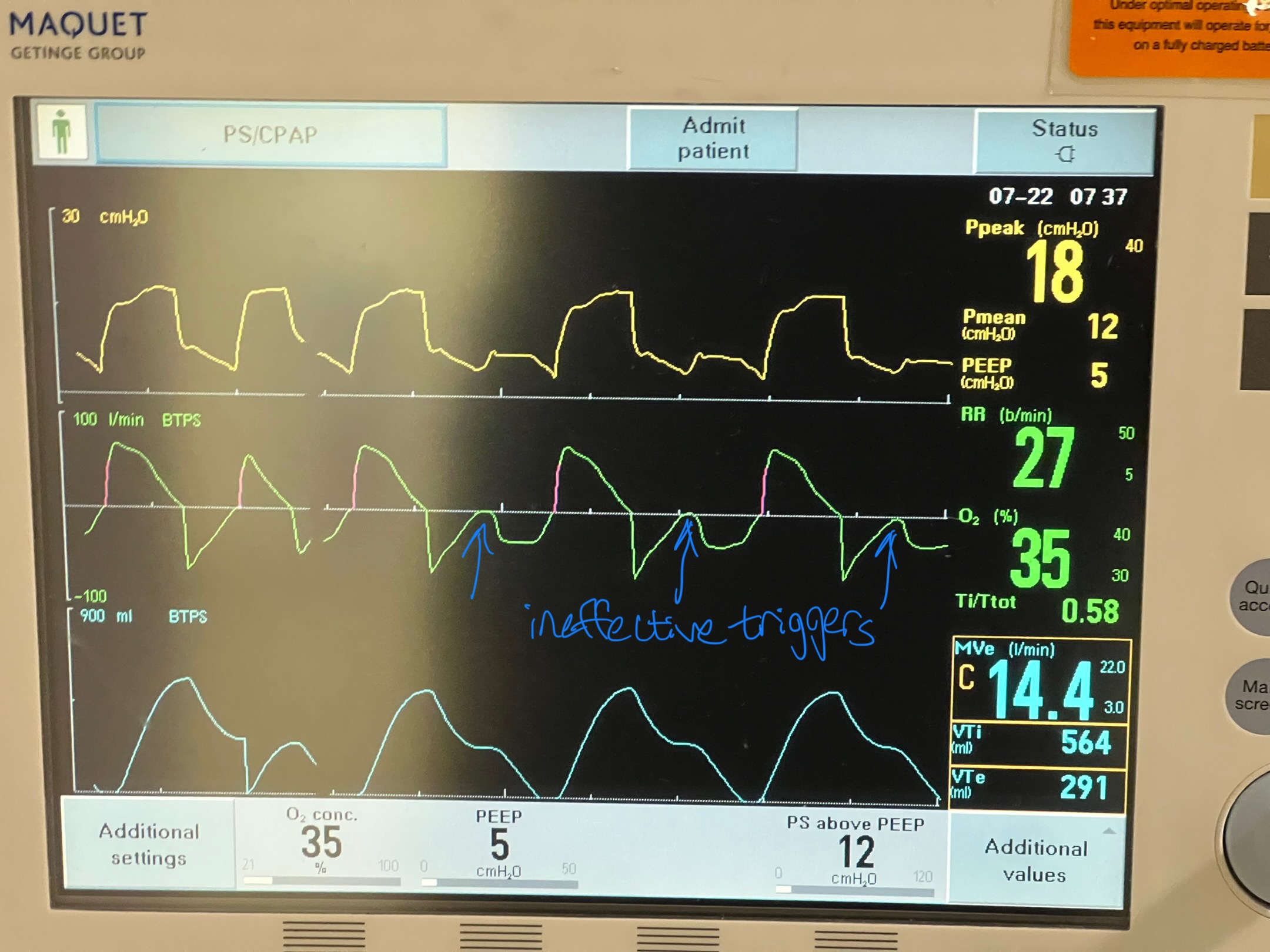

Bottom line:

If a ventilated patient exhibits at least one of: persistent end expiratory flow, unequal inspiratory and expiratory flow-time areas, or ineffective breath triggers; autoPEEP must be evaluated by performing an end-expiratory hold.

If present, ventilator settings should be changed to maximize exhalation time.

In critically ill patients with obstructive lung disease, intubation and mechanical ventilation is often a last resort as it does not fix the underlying pathology of small airway disease. While many complications can arise, the most feared complication is autoPEEP.

What is autoPEEP?

AutoPEEP is excess air trapping in the lungs because the patient has insufficient time to fully exhale. Patients at highest risk include those with obstructive lung pathology due to their increased resistance (from bronchospasm) and sometimes increased compliance (such as in emphysema).

However, it is possible for any patient to develop autoPEEP depending on the amount of time they have to exhale. As respiratory rate increases, the expiratory time decreases proportionally if inspiratory time is kept constant. Ultimately, autoPEEP can lead to rapidly increasing intrathoracic pressures causing decreased preload leading to hemodynamic instability and potentially cardiac arrest. These elevated pressures also place the patient at significant risk of barotrauma/volutrauma.

How do I find it?

There are several signs on the ventilator waveforms for autoPEEP. Some patients may only exhibit one of the following signs of autoPEEP. They are demonstrated in the attached pictures in various ventilator modes.

Image A. Persistent end expiratory flow on the flow-time curve (middle curve) - demonstrated by the expiratory limb of the flow curve not returning to zero (remains negative)

Image B. Unequal inspiratory and expiratory volumes on the flow-time curve (area of flow curve inspiratory limb does not equal area of flow curve expiratory limb)

Image C. Ineffective triggering (seen on flow-time curve; patient has to perform more work to reach trigger threshold when autoPEEP is present; they are sometimes unable to trigger a breath)

If any of these are present, an end-expiratory hold maneuver should be performed.

Image D - End-expiratory hold maneuver (done if patient is passive on the ventilator) - the pressure-time curve will begin at ventilator set PEEP and reach total PEEP at the end of the maneuver. The difference between total PEEP and set PEEP is autoPEEP.

If autoPEEP is present, ventilator changes to allow for more exhalation time should be made. The most effective change is by decreasing the respiratory rate though small improvements can be made by changing the inspiratory time and tidal volume. Appropriate bronchodilator therapy, sedation, and treatment of underlying pathology is also critical in these patients.

For more information on autoPEEP, check out this post by Dr. John Greenwood discussing autoPEEP on MarylandCCProject with video demonstrations!

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 10/21/2025 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Check for Elevated ICP in the Post-ROSC Patient

Long B, Gottlieb M. Emergency medicine updates: Managing the patient with return of spontaneous circulation. Am J Emerg Med. 2025; 26-36.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: delirium, ICU, acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (PubMed Search)

Posted: 10/14/2025 by Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

(Updated: 2/1/2026)

Click here to contact Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

Delirium is common among critically ill patients. Some of the common Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEI), rivastigmine, donepezil, have been used to prevent delirium in ICU patients. However, their efficacy was just recently re-examined in a meta-analysis of only Randomized Control Trials.

Ten studies and 731 patients were included- 365 in the treatment (AChEI) group and 366 in the control group.

AChEI was associated with lower occurrence of delirium (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.47-0.98, p=0.039. However, there was no significant difference in the delirium duration (mean difference -0.16 day, 95% CI -0.95 to 0.62 day, p=0.23). There was no difference in delirium severity nor length of hospital stay.

Among the medication, interestingly, rivastigmine 4.5 mg/day significantly reduced delirium occurrence (RR = 0.61 [0.39– 0.97]) and severity (SMD = –0.33 [–0.58 to –0.08]), as well as length of hospital stay (MD = –1.29 [–1.87 to –0.72]).

Discussion:

This meta-analysis was well-conducted.

The cholinergic dysregulation—especially elevated acetylcholinesterase activity—can lead to the imbalance between attention and cognition, contributing to delirium in ICU patients. Thus, the use of AChEI and reduction of occurrence of delirium proves that acetylcholine deficiency may be associated with delirium among ICU patients.

Subgroup analysis showed that prophylactic use of AChEI was associated with significant reduction of delirium duration. Thus, further studies are needed to define which populations will benefit from AChEI.

Conclusion:

AChEIs are effective in reducing occurrence of delirium, but they did not affect delirium duration, severity or hospital LOS.

Pipek LZ, Pascual GS, Nascimento RFV, Silva GD, Castro LH. Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors for Delirium Prevention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med. 2025 Oct 1;53(10):e2054-e2061. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000006786. Epub 2025 Aug 5. PMID: 40758382.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: acute respiratory failure, hypercapnia, hypercarbia, COPD, AE-COPD, noninvasive ventilation, high flow nasal cannula (PubMed Search)

Posted: 10/7/2025 by Kami Windsor, MD

Click here to contact Kami Windsor, MD

Q: Can you use high flow nasal cannula (HFNC) to manage acute hypercapnic respiratory failure?

A: It probably depends.

Background: While we now frequently utilize HFNC as an initial therapy for most acute hypoxic respiratory failure, its appropriateness in managing acute respiratory failure with hypercarbia has historically been opposed. With more recent data indicating that HFNC may be as good as noninvasive ventilation (NIV) for management of hypercapnia as well, this seemed like a good time to point out a few things:

The RENOVATE trial was a larger multicenter randomized noninferiority trial looking at HFNC vs NIV in all-comer acute respiratory failure, summarizing that HFNC was noninferior in the primary composite outcome of death + intubation at 7 days.

BUT this conclusion is not clearly supported in the smaller COPD (or acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema) subgroup:

What does seem to be clear across studies that HFNC has the capacity to clear some CO2 and is by and large better tolerated than facemask NIV.

Bottom Line: For mild-moderate acute COPD exacerbations with patient intolerance or exclusion criteria for NIV therapy, trialing HFNC is a reasonable option. For patients with severe acute or acute on chronic hypercapnia, as indicated by a [pseudo-arbitrary] pH < 7.25 and PaCO2 >70-80, noninvasive ventilation should be your go-to… or be ready to promptly intubate if/when the high flow fails.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: sepsis, septic shock, omeprazole, proton pump inhibitor, anti-inflammatory (PubMed Search)

Posted: 9/30/2025 by Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

Click here to contact Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

Settings: multinational, randomized, double- blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted in 17 centers in Italy, Russia, and Kazakhstan

Participants: A total of 307 ICU patients with sepsis or septic shock. Patients who were likely to die (APACHE II > 65 points) were excluded.

Treatment group: 80 mg bolus of omeprazole at randomization, at 12 hours and infusion of 12 mg/hour for 72 hours. Total dose of 1024 mg.

Outcome measurement: primary outcome of the study was organ dysfunction measured as the mean daily SOFA score during the first 10 days. Secondary outcomes were antibiotics-free days at 28 days; all-cause mortality at 28 days

Study Results:

Discussion:

Conclusion:

In sepsis patients, Esomeprazole did not re- duce organ dysfunction, despite demonstrating in vivo immunomodulatory effects

Monti G, Carta S, Kotani Y, Bruni A, Konkayeva M, Guarracino F, Yakovlev A, Cucciolini G, Shemetova M, Scapol S, Momesso E, Garofalo E, Brizzi G, Baldassarri R, Ajello S, Isirdi A, Meroi F, Baiardo Redaelli M, Boffa N, Votta CD, Borghi G, Montrucchio G, Rauch S, D'Amico F, Pace MC, Paternoster G, Vitale F, Giardina G, Labanca R, Lembo R, Marmiere M, Marzaroli M, Nakhnoukh C, Plumari V, Scandroglio AM, Scquizzato T, Sordoni S, Valsecchi D, Agrò FE, Finco G, Bove T, Corradi F, Likhvantsev V, Longhini F, Konkayev A, Landoni G, Bellomo R, Zangrillo A; PPI-SEPSIS Study Group. A Multinational Randomized Trial of Mega-Dose Esomeprazole as Anti-Inflammatory Agent in Sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2025 Aug 1;53(8):e1554-e1566. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000006720. Epub 2025 May 29. PMID: 40439536.