Category: Pediatrics

Keywords: Bronchiolitis, wheezing (PubMed Search)

Posted: 12/19/2014 by Jenny Guyther, MD

Click here to contact Jenny Guyther, MD

Now that respiratory season is upon us, we are faced with an increasing number of bronchiolitis children. The updated clinical practice guidelines for managing these kids were recently published and emphasize supportive care only.

Some of the key points:

-When clinicians diagnose bronchiolitis on the basis of history and physical examination, radiographic or laboratory studies should not be obtained routinely.

-Medications such as albuterol, nebulized epinephrine or steroids should not be administered routinely in children with a diagnosis of bronchiolitis.

-Nebulized hypertonic saline should not be administered to infants with a diagnosis of bronchiolitis in the emergency department

-Clinicians may choose not to administer supplemental oxygen if the oxyhemoglobin saturation exceeds 90% in infants and children with a diagnosis of bronchiolitis

-Clinicians may choose not to use continuous pulse oximetry for infants and children with a diagnosis of bronchiolitis.

Check out the full guidelines for the quality of evidence and rational behind these recommendations.

The bottom line is that not much really works, and we just need to support their respiratory effort and ensure hydration.

Ralston et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: The diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Bronchiolitis. Pediatrics 2014; 134: e1474-e1502.

Category: Pediatrics

Posted: 12/13/2014 by Rose Chasm, MD

(Updated: 1/31/2026)

Click here to contact Rose Chasm, MD

NMS Pediatrics. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. 4th Edition. Paul Dworkin editor.

Category: Pediatrics

Keywords: dehydration (PubMed Search)

Posted: 11/28/2014 by Mimi Lu, MD

Click here to contact Mimi Lu, MD

Dehydration is a common pediatric ED presentation. Oral rehydration (although first choice) is often not possible secondary to patient cooperation and/ or persistent vomiting. Intravenous (IV) hydration is often difficult, requiring multiple attempts especially in the young dehydrated infant.

Hyaluronan is a mucopolysaccharude present in connective tissue that prevents the spread of substances through the subcutneous space. Hyaluronidase is a human DNA-derived enzyme that breaks down hyaluronan and temporarily increases its permeability, thereby allowing fluid to be absorbed with the capillary and lymphatic systems.

In one study, patients age 1 month to 10 years were randomized to recieve 20 mL/kg bolus NS via subcutaneous (SC) or IV route over one hour, then as needed. The mean volume infused in the ED was 334.3 mL (SC) vs 299.6 mL (IV). Succesful line placement occured in all 73 SC patients and only 59/75 IV patients. There was a higher proportion of satisfaction for clinicians and parents for ease of use and satisfaction, respectively.

Bottom line: Consider subcutaneous hyaluronidase faciliated rehydration in mild to moderately dehydrated children, especially with difficult IV access.

Spandorfer PR, et al. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Recombinant Human Hyaluronidase-Fcilitated Subcutaneous Versus Intravenous Rehydration in Mild to Moderately Dehydrated Children in the Emergency Department. Clinical Therapeutics, 2012; 34(11): 2232-2245.

Category: Pediatrics

Keywords: Medications, overdose, pediatric, over the counter (PubMed Search)

Posted: 11/21/2014 by Jenny Guyther, MD

Click here to contact Jenny Guyther, MD

Category: Pediatrics

Keywords: appendicitis, ultrasound, bedside (PubMed Search)

Posted: 11/8/2014 by Ashley Strobel, MD

Click here to contact Ashley Strobel, MD

Emergency Physician Bedside Ultrasound for Appendicitis

Why?

To reduce length of stay, improve patient care, and reduce radiation exposure in young patients.

How?

Start with pain medication so you get a better study. (Consider intranasal fentanyl for quicker pain relief and diagnostics in pediatrics.) Study results are also improved with a slim body habitus.

Place the patient supine

Use a high-frequency linear array transducer

Start at the point of maximal tenderness in the RLQ

Transverse and longitudinal planes "graded compression" to displace overlying bowel gas which usually has peristalsis (See Sivitz, et al article for images of "graded compression")

Appendix is usually anterior to the psoas muscle and iliac vein and artery as landmarks

Measure from outer wall to outer wall at the most inflamed portion of the appendix (usually distal end)

Example:

Positive study:

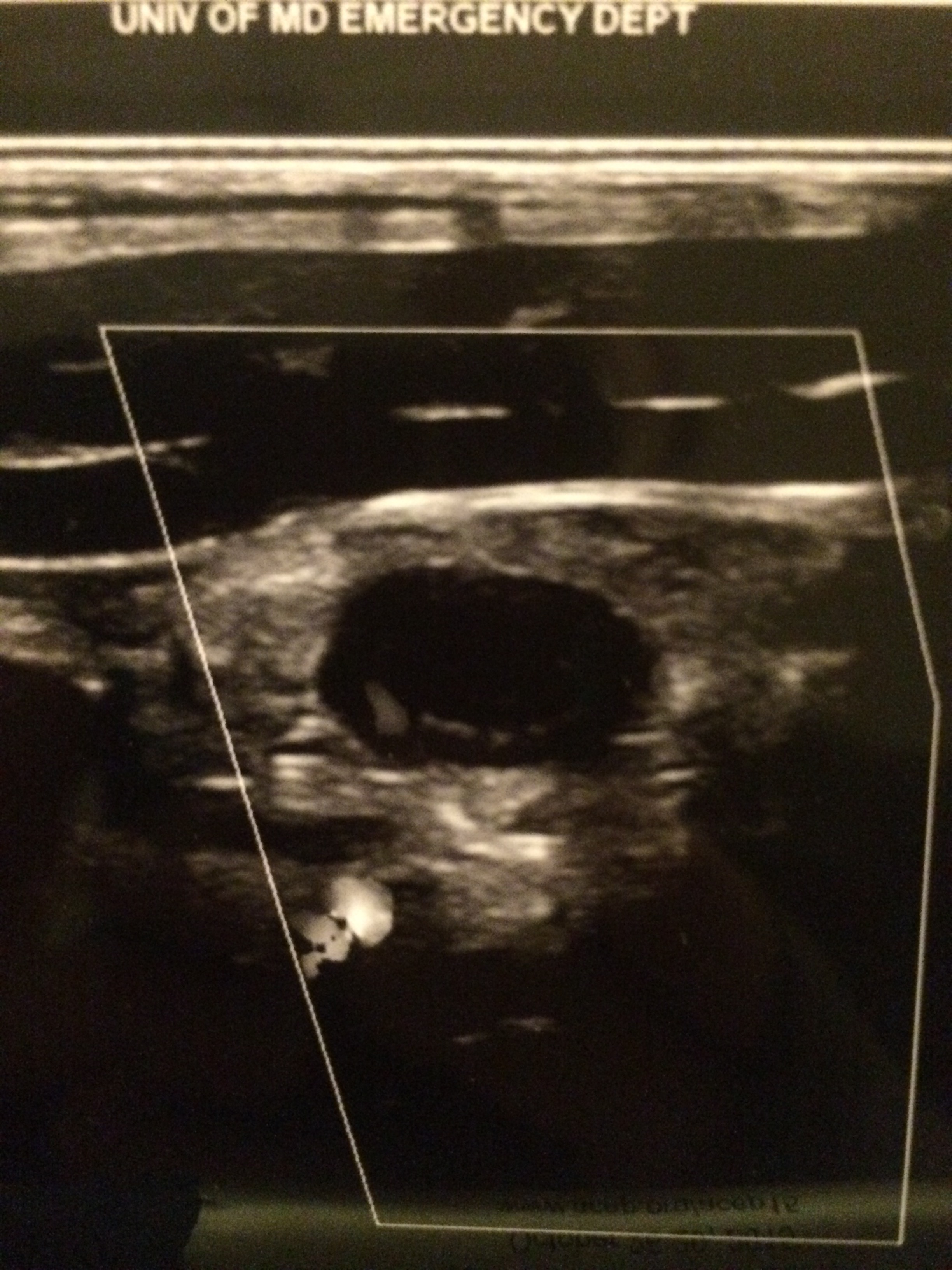

A non-compressible, blind-ending tubular structure in the longitudinal axis >6 mm without peristalsis (see second image above with 8.3 mm diameter measurement)

A target sign in the transverse view (see first image above)

Additional suggestive findings: appendiceal wall hyperemia with color Doppler, appendicoliths hyperechoic (white) foci with an anechoic (black) shadow, periappendiceal inflammation or free fluid

Negative study:

Non-visualization of the appendix with adequate graded compression exam in the absence of free fluid or inflammation.

Limitations for visualization and possible false negative result:

Retrocecal appendix and perforated appendix are difficult to visualize with US.

Pitfalls:

US has good specificity (93% in Sivitz et al article), but limited sensitivity (85% in Sivitz et al article), so trust your clinical judgement. You may need a MRI (pregnant/pediatrics) or CT as they have improved, but not perfect sensitivity.

Valesky, et al. Focus On: Ultrasound for Appendicitis. ACEP Now. June 2012.

Sivitz AB, Cohen SG, Tejani C. Evaluation of Acute Appendicitis by Pediatric Emergency Physician Sonography. Annals of Emerg Med. Oct 2014; 64: 358-363.

Category: Pediatrics

Keywords: Lactate (PubMed Search)

Posted: 10/17/2014 by Jenny Guyther, MD

(Updated: 1/31/2026)

Click here to contact Jenny Guyther, MD

The world of pediatrics is still working on catching up to adult literature in terms of lactate utilization and its implications. The study referenced looked at over 1000 children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit. Lactate levels were collected 2 hours after admission and a mortality risk assessment was calculated within 24 hours of admission (PRISM III). Results showed that the lactate level on admission was significantly associated with mortality after adjustment for age, gender and PRISM III score.

Bottom line: In your critically ill pediatric patient, lactate may be a useful predictor of mortality.

Bai Z et al. Effectiveness of predicting in-hospital mortality in critically ill children by assessing blood lactate levels at admission. BMC Pediatrcs 2014; 14:83.

Category: Pediatrics

Posted: 10/10/2014 by Rose Chasm, MD

(Updated: 1/31/2026)

Click here to contact Rose Chasm, MD

Bennett NJ, et al. Pediatric Pneumonia Treatment and Management. Medscape. April 2014.

AAP. Management of Communty-Acquired Pneumonia in Infants and Children Older than 3 Months of Age. Pediatrics. Vol 128 No 6 December 1, 2011.

Category: Pediatrics

Keywords: E. coli, O0157:H7, hematochezia, diarrhea (PubMed Search)

Posted: 9/26/2014 by Mimi Lu, MD

Click here to contact Mimi Lu, MD

There are numerous different causes of pediatric hemorrhagic diarrhea. Consider a pediatric patient with bloody diarrhea as being at risk for developing hemolytic uremic syndrome. Most cases of hemolytic uremic syndrome are caused by O157:H7 strains of E Coli that release Shiga-like toxin from the gut. Systemic release of the toxin causes microvascular thromboses in the renal microvasculature. The characteristic microangiopathic hemolysis results with anemia, thrombocytopenia and peripheral schistocytes seen on laboratory studies, in addition to acute renal failure.

Antibiotics have been controversial in the treatment of pediatric hemorrhagic diarrhea due to concern that they worsen toxin release from children infected with E Coli O157:H7 and thus increase the risk of developing hemolytic uremic syndrome. Numerous previous studies have provided conflicting data regarding the true risk (1). A recent prospective study showed antibiotic treatment increases the risk (2). Most recommendations warn against using antibiotics to treat pediatric hemorrhagic diarrhea unless the patient is septic.

Bottom line: Avoid treating pediatric hemorrhagic diarrhea with antibiotics

References:

1. Systematic review: are antibiotics detrimental or beneficial for the treatment of patients with Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection? Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. Volume 24, Issue 5, pages 731–742, September 2006

2. Risk factors for the hemolytic uremic syndrome in children infected with Escherichia coli O157:H7: a multivariable analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012 Jul;55(1):33-41. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis299. Epub 2012 Mar 19.

Category: Pediatrics

Keywords: Macklin Phenomenon, asthma, pneumomediastinum (PubMed Search)

Posted: 9/22/2014 by Ashley Strobel, MD

Click here to contact Ashley Strobel, MD

16 yo M with pleuritic right upper chest pain that started today. He is suffering from an asthma exacerbation currently in the setting of URI with cough. He is afebrile, tachycardic to 140-150s, respiratory rate 20, and sats 98% on room air. ECG was performed which incidentally diagnosed this patient WPW and he went for ablation as an outpatient. His chest x-ray showed:

Besides a bad day, what do we call this chest x-ray finding?

Macklin Phenomenon

-asthma exacerbation rupture of the alveoli causing pneumomediastinum

-typically a young man

-most common chief complaint is chest pain

Physical Exam: Hamman’s sign may be present (crackle with heartbeat) or subcutaneous emphysema

Etiology: Esophagus, lungs, or bronchial tree

Rupture of alveoli: asthma exacerbation (bronchial hyper-reactivity/constriction), barotrauma, valsalva maneuvers (lifting, childbirth), deep respiratory maneuvers/Valsalva (strenuous exercise or FVC breathing), drug use (crack cocaine causing bronchial constriction, marijuana), vomiting, blunt thoracic/abdominal trauma, scuba diving with rapid ascent

Aerodigestive tract injuries: bronchoscopy tracheobronchial injuries, laryngeal fx, bronchial fx, tracheal neoplasm, esophageal injuries (Boerhaave syndrome, paripartum, asthma exacerbation, esophageal neoplasm)

Extension from neck: head/neck sx, RPA/PTA, dental abscess/extractions

Extension from RP/chest wall: rupture RP hollow viscus

Management:

-self -limited

-treat underlying condition

-swallow study for all cases following emesis to rule out Boerhaave’s syndrome

-no repeat CXR, advance diet as tolerated, 23 hour observation

-Al-Mufarrei, et al suggest without trauma, pleural effusion, hemodynamic instability, pneumoperitoneum, or severe vomiting, the finding of spontaneous pneumomediastinum (with or without Meckler’s triad of esophageal rupture: vomiting, lower chest pain, and cervical subcutaneous emphysema after overindulgence) usually leads to unnecessary radiologic investigations, dietary restriction, and antibiotic administration

-surgery for decompression

Gray JM and Hanson GC. Mediastinal emphysema: aetiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Thorax. 1966; 21: 325-332.

Al-Mufarrej F, Badar J, Gharagozloo F, Tempesta B, Strother E, Margolis M. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: diagnostic and therapeutic intervnetions. Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery. November 2008; 3: 59.

Category: Pediatrics

Keywords: cervical spine, pediatrics, NEXUS (PubMed Search)

Posted: 9/19/2014 by Jenny Guyther, MD

(Updated: 1/31/2026)

Click here to contact Jenny Guyther, MD

The NEXUS criteria is widely applied to adults who present with neck pain due to trauma. While this study did include about 2000 pediatric patients, there were not enough young children to draw definitive conclusions. For more information on the evaluation of the cervical spine, see Dr. Rice's pearl from 9/7/12. A 2003 study piloted an algorithm for cervical spine clearance in children < 8 years.

Patients were spine immobilized if: unconscious, abnormal neurological exam, history of transient neurological symptoms, significant mechanism of injury, neck pain, focal neck tenderness or inability to assess based on distracting injury (extremity or facial fractures, open wound, thoracic injuries, or abdominal injuries), physical exam findings of neck trauma, unreliable exam due to substance abuse, significant trauma to the head or face, or inconsolable children.

When the 2 pathways (see attached) were implemented, there was a decrease in time to cervical spine clearance. There were no missed injuries in the study period prior to implementation of the pathway or once it was implemented. There was no significant difference in the amount of xrays, CT scans or MRIs.

Lee S, Sena M, Greenholtz, S, Fledderman M. A Multidisciplinary Approach to the Development of a Cervical Spine Clearance Protocol: Process, Rationale, and Initial Results. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 2003; 38 (3): 358-362.

Category: Pediatrics

Posted: 9/12/2014 by Rose Chasm, MD

(Updated: 1/31/2026)

Click here to contact Rose Chasm, MD

Severe Respiratory Illness Associated With Enterovirus D68--Missouri and Illinois, 2014. CDC MMWR. Vol 63. September 2014.

Category: Pediatrics

Keywords: URI, sinusitis (PubMed Search)

Posted: 8/15/2014 by Jenny Guyther, MD

Click here to contact Jenny Guyther, MD

6-7% of kids presenting with upper respiratory symptoms will meet the definition for ABS.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) reviewed the literature and developed clinical practice guideline regarding the diagnosis and management of ABS in children and adolescents.

The AAP defines ABS as: persistent nasal discharge or daytime cough > 10 days OR a worsening course after initial improvement OR severe symptom onset with fever > 39C and purulent nasal discharge for 3 consecutive days.

No imaging is necessary with a normal neurological exam.

Treatment includes amoxicillin with or without clauvulinic acid (based on local resistance patterns) or observation for 3 days.

Optimal duration of antibiotics has not been well studied in children but durations of 10-28 days have been reported.

If symptoms are worsening or there is no improvement, change the antibiotic.

There is not enough evidence to make a recommendation on decongestants, antihistamines or nasal irrigation.

Wald et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis in Children Aged 1 to 18 Years. Pediatrics. Volume 132, Number 1, July 2013.

Category: Pediatrics

Posted: 8/9/2014 by Rose Chasm, MD

Click here to contact Rose Chasm, MD

Category: Pediatrics

Keywords: tympanostomy tubes, antibiotics, otorrhea (PubMed Search)

Posted: 7/18/2014 by Jenny Guyther, MD

Click here to contact Jenny Guyther, MD

Up to 26% of patients with tympanostomy tubes (PE tubes) can suffer from clinically manifested otorrhea. This is thought to be the result of acute otitis media that is draining through the tube. Previous small studies suggested that antibiotic ear drops are as effective or more effective and with less side effects for its treatment. This study compared treatment with antibiotic/glucocorticoid ear drops (hydrocortisone-bacitracin-

Study population: Children 1-10 years with otorrhea for up to 7 days in the Netherlands

Exclusion criteria included: T > 38.5 C, antibiotics in previous 2 weeks, PE tubes placed within 2 weeks, previous otorrhea in past 4 weeks, 3 or more episodes of otorrhea in past 6 months

Patient recruitment: ENT and PMD approached pt with PE tubes and they were told to call if otorrhea developed and a home visit would be arranged

Study type: open-label, pragmatic, randomized control trial

Primary outcome: Treatment failure defined as the presence of otorrhea observed otoscopically

Secondary outcome: based on parental diaries of symptoms, resolution and recurrence over 6 months

Results: After 2 weeks, only 5% of the ear drop group compared to 44% of the oral antibiotic group and 55% of the observation group still had otorrhea. There was not a significant difference between those treated with oral antibiotics and those that were observed. Otorrhea

lasted 4 days in the ear drop group compared to 5 days with oral antibiotics and 12 days with observation (all statistically significant).

Key differences: The antibiotic dosing and choice of ear drops are based on availability and local organism susceptibility.

Bottom line: For otorrhea in the presence of PE tubes, ear drops (with a non-aminoglycoside antibiotic and a steroid) may be more beneficial than oral antibiotics or observation.

van Dongen TM, van der Heijden GJ, Venekamp RP, Rovers MM, Schilder AG. A trial of treatment for acute otorrhea in children with tympanostomy tubes. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:723-33.

Category: Pediatrics

Posted: 7/11/2014 by Rose Chasm, MD

(Updated: 1/31/2026)

Click here to contact Rose Chasm, MD

Wolfe TR, Braude DA. Intranasal Medication Delivery for Children: A Review and Update. Pediatrics. 2010;126:532-7.

Mudd S. Intranasal fentanyl for pain management in children: a systematic review of the literature. J PediatrHealth Care 2011;25:316-22.

Chiaretti A, Barone G, Rigante D, et al. Intranasal lidocaine and midazolam for procedural sedation in children. Arch Dis Child 2011;96:160-3.

Category: Pediatrics

Keywords: Ultrasound, pediatrics, appendicitis (PubMed Search)

Posted: 6/20/2014 by Jenny Guyther, MD

Click here to contact Jenny Guyther, MD

Category: Pediatrics

Keywords: Psychiatric clearance, pediatric (PubMed Search)

Posted: 5/16/2014 by Jenny Guyther, MD

Click here to contact Jenny Guyther, MD

Mental health-related visits account for 1.6–6% of ED encounters. Patients with acute psychosis are often brought to the ED for clearance prior to psychiatric evaluation. Is this necessary?

Background: Several adult studies have shown that only 0–4% of patients with isolated psychiatric complaints have organic diagnoses requiring urgent treatment. Routine ED laboratory testing in adults is low yield still, with one study identifying abnormalities in only 2 of 352 patients—both mild hypokalemia. A pediatric study found that 207 of 209 patients were medically cleared.

This study was a retrospective review of pediatric psychiatric patients presenting to a an urban California hospital. They examined 798 patients who had an involuntary psychiatric hold placed by a psychiatric mobile response team.

The authors concluded that few pediatric patients brought to the ED on an involuntary hold required a medical screen and perhaps use of basic criteria in the prehospital setting to determine who required a medical screen (altered mental status, ingestion, hanging, traumatic injury, unrelated medical complaint, sexual assault) could have led to significant savings.

Santillanes, G et al. Is Medical Clearance Necessary for Pediatric Psychiatric Patients? J Emerg Med. 2014 Mar 15. pii: S0736-4679(13)01455-8. [Epub ahead of print]

Category: Pediatrics

Keywords: scabies, pediatrics (PubMed Search)

Posted: 4/18/2014 by Jenny Guyther, MD

Click here to contact Jenny Guyther, MD

Scabies is considered by the WHO to be one of the main neglected diseases with approximately 300 million cases worldwide each year. One third of cases of scabies seen by dermatologists are in kids less than 16 years old. The belief had been that presentation varies by age. One French study reported a first time miss rate of more than 41% and an overall diagnostic delay of 62 days.

A prospective, multi center observational study of patients with confirmed scabies sought to determine common phenotypes in children. All patients were seen by dermatologists in France and administered standard questionnaires. They were divided into 3 age groups, <2 years, 2-15 years and > 15 years. 323 patients were included.

The study found that:

-infants were more likely to have facial involvement and nodules, especially on the back and axilla

-relapse was more common in < 15 year olds - this was hypothesized to be due to poor compliance with treatment to the head

-family members with itch, or planter or scalp involvement were independently associated with diagnosis of scabies in kids < 2 years

-burrows were seen in 78%, nodules in 67% and vesicles of 43% of patients (see photo)

-itching was absent in up to 10% of patients

Bottom line: Have a high suspicion for scabies in any rash.

Category: Pediatrics

Posted: 4/11/2014 by Rose Chasm, MD

(Updated: 1/31/2026)

Click here to contact Rose Chasm, MD

Category: Pediatrics

Keywords: Head injury, vomiting, PECARN (PubMed Search)

Posted: 3/21/2014 by Jenny Guyther, MD

Click here to contact Jenny Guyther, MD