Category: Critical Care

Keywords: POCUS, Massive PE (PubMed Search)

Posted: 6/6/2017 by Rory Spiegel, MD

(Updated: 2/1/2026)

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

The poor sensitivity of bedside echocardiography to identify all-comers with pulmonary embolism is well documented. Most series cite a sensitivity and specificity of 31% to 72% and 87% to 98%, respectively (1,2). But as Nazerian et al demonstrate in their recent publication in Internal and Emergency Medicine, the diagnostic performance of bedside echocardiography is far more reliable in the subset of patients presenting in shock (3).

Of the 105 patients included in the final analysis, in 43 (40.9%) PE was determined to be the etiology of their shock. Bedside echo demonstrated notable diagnostic prowess when employed in this subset of patients, sensitivity (91%), specificity (87%), –LR (0.11), +LR (7.03). The sensitivity and –LR were further augmented when the venous US of the LE was included (sensitivity of 95% and –LR of 0.06) in the diagnostic workup.

1. Dresden S, Mitchell P, Rahimi L, et al. Right ventricular dilatation on bedside echocardiography performed by emergency physicians aids in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63(1):16-24.

2. Nazerian P, Vanni S, Volpicelli G, et al. Accuracy of point-of-care multiorgan ultrasonography for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Chest. 2014;145(5):950-957.

3. Nazerian P, Volpicelli G, Gigli C, Lamorte A, Grifoni S, Vanni S. Diagnostic accuracy of focused cardiac and venous ultrasound examinations in patients with shock and suspected pulmonary embolism. Intern Emerg Med. 2017;

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Hyperoxia, Mechanical Ventilation (PubMed Search)

Posted: 4/11/2017 by Rory Spiegel, MD

(Updated: 2/1/2026)

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

The deleterious effects of hyperoxia are becoming more and more apparent. But obtaining a blood gas to ensure normoxia in a busy Emergency Department can be burdensome. And while the utilization of a non-invasive pulse oximeter seems ideal, the threshold that best limits the rate of hyperoxia is unclear.

Durlinger et al in a prospective observational study demonstrated that an oxygen saturation 95% or less effectively limited the number of patients with hyperoxia (PaO2 of greater than 100 mm Hg). Conversely when an SpO2 of 100% was maintained, 84% of the patients demonstrated a PaO2 of greater than 100 mm Hg.

Durlinger EM, Spoelstra-de man AM, Smit B, et al. Hyperoxia: At what level of SpO2 is a patient safe? A study in mechanically ventilated ICU patients. J Crit Care. 2017;

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: lung protective ventilation, ARDS (PubMed Search)

Posted: 3/21/2017 by Rory Spiegel, MD

(Updated: 2/1/2026)

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

While lung protective ventilatory strategies have long been accepted as vital to the management of patients undergoing mechanical ventilation, the translation of such practices to the Emergency Department is still limited and inconsistent.

Fuller et al employed a protocol ensuring lung-protective tidal volumes, appropriate setting of positive end-expiratory pressure, rapid weaning of FiO2, and elevating the head-of-bed. The authors found the number of patients who had lung protective strategies employed in the Emergency Department increased from 46.0% to 76.7%. This increase in protective strategies was associated with a 7.1% decrease in the rate of pulmonary complications (ARDS and VACs), 14.5% vs 7.4%, and a 14.3% decrease in in-hospital mortality, 34.1% vs 19.6%.

Fuller BM, Ferguson IT, Mohr NM, et al. Lung-Protective Ventilation Initiated in the Emergency Department (LOV-ED): A Quasi-Experimental, Before-After Trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Ketamine, agitated delirium (PubMed Search)

Posted: 2/28/2017 by Rory Spiegel, MD

(Updated: 2/1/2026)

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

A recently published study adds to the growing body of literature supporting the use of IV//IM ketamine as a first line agent for the control of the acutely agitated patient. In this observational cohort Riddell et al found patients given ketamine more frequently achieved adequate sedation at both 5 and 10 minutes compared to benzodiazepines, Haloperidol, given alone or in combination. This rapid sedation was achieved without an increase in the need for additional sedation or the rate of adverse events.

Riddell J, Tran A, Bengiamin R, Hendey GW, Armenian P. Ketamine as a first-line treatment for severely agitated emergency department patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2017

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: peri-Intubation hypotension, shock index (PubMed Search)

Posted: 2/7/2017 by Rory Spiegel, MD

(Updated: 2/1/2026)

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

Identifying patients at risk of hypotension during intubation is not always straight forward. The prevalence of peri-intubation hypotension in the Emergency Department has been demonstrated to be approximately 20%.1 And while certain variables increase the likelihood of peri-intubation hypotension (ex. Shock index> 0.80), no single factor predicts it accurately enough to be used at the bedside.2 In the majority of patients undergoing intubation, clinicians should be prepared for peri-intubation hypotension with either vasopressor infusions or push dose pressors.

1. Heffner AC, Swords D, Kline JA, Jones AE. The frequency and significance of postintubation hypotension during emergency airway management. J Crit Care. 2012;27(4):417.e9-13.

2. Heffner AC, Swords DS, Nussbaum ML, Kline JA, Jones AE. Predictors of the complication of postintubation hypotension during emergency airway management. J Crit Care. 2012;27(6):587-93.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Arterial Line, Ultrasound (PubMed Search)

Posted: 1/17/2017 by Rory Spiegel, MD

(Updated: 2/1/2026)

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

It is not uncommon for critically ill patients to require invasive monitoring of their blood pressure. In these patients, radial arterial lines are often inserted. Traditionally these lines are placed using palpation of the radial pulse. This technique can lead to unacceptably high failure rate in the hypotensive patient commonly encountered in the Emergency Department.

A recent meta-analysis by Gu et al demonstrated the use of dynamic US to assist in the placement of radial arterial lines decreased the rate of first attempt failure, time to line insertion and the number of adverse events associated with insertion.

Gu WJ, Wu XD, Wang F, Ma ZL, Gu XP. Ultrasound Guidance Facilitates Radial Artery Catheterization: A Meta-analysis with Trial Sequential Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Chest. 2016;149(1):166-79.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Acute pulmonary edema, Bolus nitrates (PubMed Search)

Posted: 12/27/2016 by Rory Spiegel, MD

(Updated: 2/1/2026)

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

It is well known that the early aggressive utilization of IV nitrates and non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIV) in patients presenting with acute pulmonary edema will decrease the number of patients requiring endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation.

Often our tepid dosing of nitroglycerine is to blame for treatment failure. Multiple studies have demonstrated the advantages of bolus dose nitroglycerine in the early management of patients with acute pulmonary edema. In these cohorts, patients bolused with impressively high doses of IV nitrates every 5 minutes, are intuabted less frequently than patients who received a standard infusion (1,2). No concerning drops in blood pressure in the patients who received bolus doses of nitrates were observed. Using the standard 200 micrograms/ml nitroglycerine concentration, blood pressure can be rapidly titrated to effect.

1. Cotter G, Metzkor E, Kaluski E, et al. Randomised trial of high-dose isosorbide dinitrate plus low-dose furosemide versus high-dose furosemide plus low-dose isosorbide dinitrate in severe pulmonary oedema. Lancet. 1998;351(9100):389-93.

2. Levy P, Compton S, Welch R, et al. Treatment of severe decompensated heart failure with high-dose intravenous nitroglycerin: a feasibility and outcome analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50(2):144-52

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: OHCA, ROSC (PubMed Search)

Posted: 12/6/2016 by Rory Spiegel, MD

(Updated: 2/1/2026)

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

The prognosis of patients who experienced OHCA, who have not achieved ROSC by the time they present to the Emergency Department, is dismal. As such, it behooves us as Emergency Physicians to identify the few patients with a potentially survivable event. Drennan et al examined the ROC data base and identified the cohort of patients who had not achieved ROSC and were transported to the hospital. The overall survival in this cohort was 2.0%. Factors that predicted survival were initial shockable rhythm and arrest witnessed by the EMS providers. Patients arriving to the ED without ROSC, that had neither of those prognostic factors had a survival rate of 0.7%.

Drennan IR, et al. A comparison of the universal TOR Guideline to the absence of prehospital ROSC and duration of resuscitation in predicting futility from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation (2016)

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: CPR, Cardiac Arrest (PubMed Search)

Posted: 11/15/2016 by Rory Spiegel, MD

(Updated: 2/1/2026)

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

It is well documented that when left to our own respiratory devices we will consistently over-ventilate patients presenting in cardiac arrest (1). A simple and effective method of preventing these overzealous tendencies is the utilization of a ventilator in place of a BVM. The ventilator is not typically used during cardiac arrest resuscitation because the high peak-pressures generated when chest compressions are being performed cause the ventilator to terminate the breath prior to the delivery of the intended tidal volume. This can easily be overcome by turning the peak-pressure alarm to its maximum setting. A number of studies have demonstrated the feasibility of this technique, most recently a cohort in published in Resuscitation by Chalkias et al (2). The 2010 European Resuscitation Council guidelines recommend a volume control mode targeting tidal volumes of 6-7 mL/kg and a respiratory rate of 10 breaths/minute (3).

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: US, right ventricle, heart failure (PubMed Search)

Posted: 10/25/2016 by Rory Spiegel, MD

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

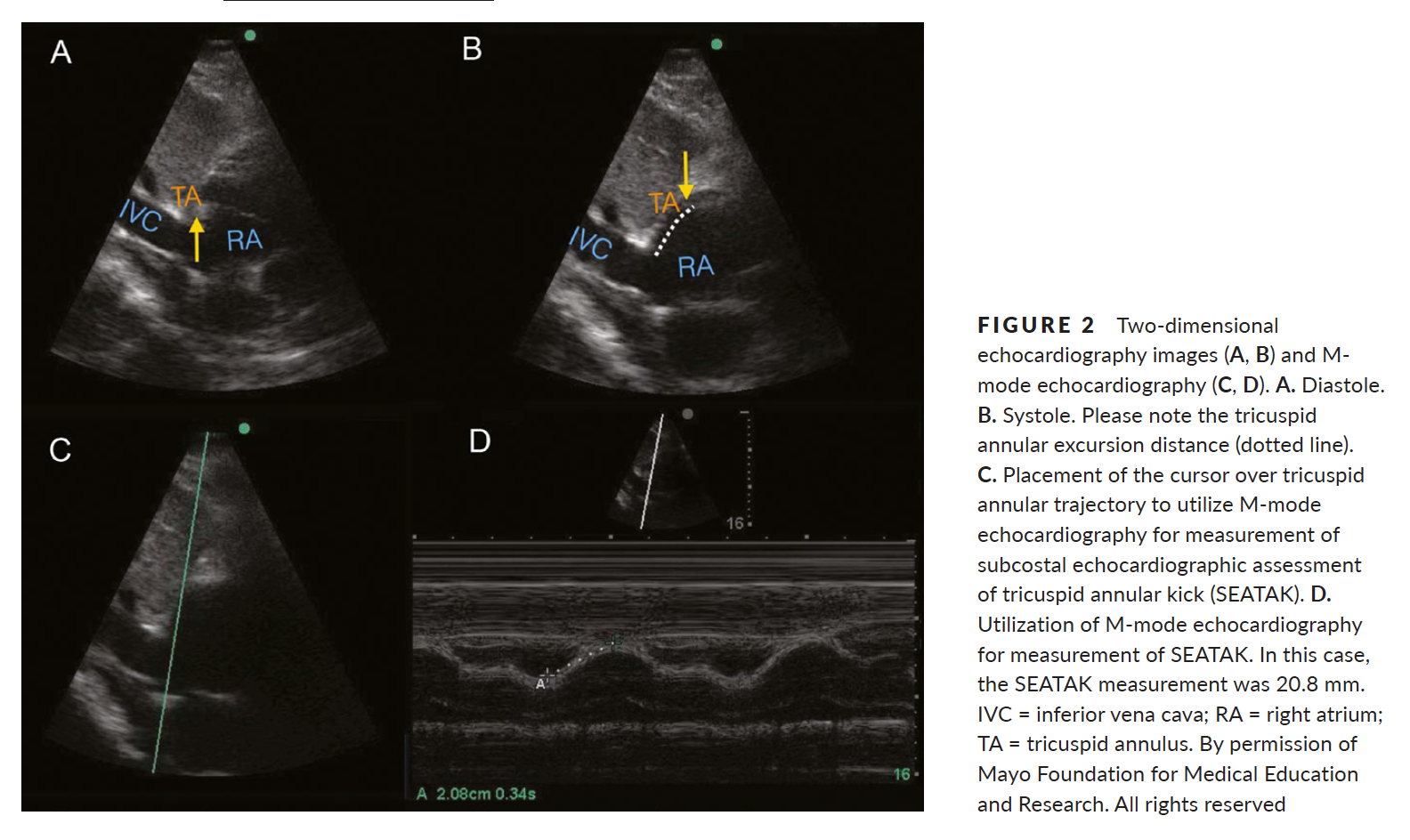

Recently Emergency Physicians have become far more aware of the importance of right ventricular (RV) function in our critically ill patient population. One of the methods that has been proposed to assess RV systolic function with bedside ultrasound (US) is the tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE). This simple bedside measurement utilizes M-mode to quantify the movement of the tricuspid annulus in systole. And while it has demonstrated reasonable accuracy at predicting RV dysfunction, adequate visualization of the lateral tricuspid annulus is not always obtainable in our critically ill patient population (1,2). In these circumstances an alternative measurement obtained in the subcostal window may be a viable option.

Similar to TAPSE, subcostal echocardiographic assessment of tricuspid annular kick (SEATAK) utilizes M-mode to assess the apical movement of the tricuspid annulus during systole. In a recent prospective observational study, Díaz-Gómez et al examined 45 ICU patients, 20 with known RV dysfunction and 25 with normal function. They compared the measurements obtained from TAPSE and SEATAK and found a strong correlation between the two measurement (Spearman’s ρ coefficient of .86, P=.03).

The small sample size and limited evaluation of RV function is far from ideal and more robust data sets are required before we cite SEATAK’s diagnostic accuracy with any confidence, but in the subset of patients where a TAPSE is unobtainable this may serve as an adequate surrogate until a more thorough echographic assessment can be obtained.

1. Ueti OM, Camargo EE, Ueti Ade A, et al. Assessment of right ventricular function with Doppler echocardiographic indices derived from tricuspid annular motion: comparison with radionuclide angiography. Heart. 2002;88:244–248.

2. Díaz-Gómez, J. L., Alvarez, A. B., Danaraj, J. J. , Freeman, M. L., Lee, A. S., Mookadam, F., Shapiro, B. P. and Ramakrishna, H. (2016), A novel semiquantitative assessment of right ventricular systolic function with a modified subcostal echocardiographic view. Echocardiography, 00: 1–9. doi: 10.1111/echo.13400.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Acid-base, SID, Delta Gap (PubMed Search)

Posted: 10/4/2016 by Rory Spiegel, MD

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

The delta gap is a measurement intended to assess for mixed acid-base disorders. A straightforward alternative, the strong ion difference (SID), allows for a quick and simple assessment of any non-gap acidosis or alkalosis that may be present.

The SID is simply the difference between the strong cations (Na+, K+, Mg+, Ca+) and the strong anions (Cl-) present in the serum. The abbreviated SID is the difference between the serum sodium and serum chloride levels (approximately 138-102). Values typically range from 36-40 mg/dl. Values less than 36 denote the presence of some degree of hyperchloremic, non-gap, acidosis. While values greater than 40 demonstrate the presence of hypochloremic, non-gap, alkalosis. And while on rare occasions, variations in albumin or elevated levels of cations other than sodium can lead you astray, the SID is as accurate as a delta gap at identifying mixed acid-based disorders without the added mathematical complexity.

Story DA. Stewart Acid-Base: A Simplified Bedside Approach. Anesth Analg. 2016;123(2):511-5.

Category: Airway Management

Keywords: RSI, Preoxygenation (PubMed Search)

Posted: 9/13/2016 by Rory Spiegel, MD

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

During rapid sequence intubation (RSI) we endeavor to avoid positive pressure ventilation, prior to securing a definitive airway. As such, an adequate buffer of oxygen is necessary to ensure a safe apneic period. This process involves replacing the residual nitrogen in the lung with oxygen. It has been demonstrated that a standard nonrebreather (NRB) mask alone does not provide a high enough fractional concentration of oxygen (FiO2) to optimally denitrogenate the lungs (1). Even when a nasal cannula at 15L/min is utilized in addition to the NRB, the resulting FiO2 is not ideal. A bag-valve mask (BVM) with a one-way valve or PEEP valve has been demonstrated to provide oxygen concentrations close to that of an anesthesia circuit. But its effectiveness is drastically reduced if a proper mask seal is not maintained during the entire pre-oxygenation period (1). This is not always logistically possible in the chaos of an Emergency Department intubation.

A standard NRB with the addition of flush-rate oxygen appears to be a viable alternative. Recently published in Annals of Emergency Medicine, Driver et al demonstrated that a NRB with wall oxygen flow rates increased to maximum levels, rather than the standard 15L/min, provided end-tidal O2 (ET-O2) levels similar to an anesthesia circuit (2).

1. Hayes-bradley C, Lewis A, Burns B, Miller M. Efficacy of Nasal Cannula Oxygen as a Preoxygenation Adjunct in Emergency Airway Management. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(2):174-80.

2. Driver BE, Prekker ME, Kornas RL, Cales EK, Reardon RF. Flush Rate Oxygen for Emergency Airway Preoxygenation. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: DKA (PubMed Search)

Posted: 8/23/2016 by Rory Spiegel, MD

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

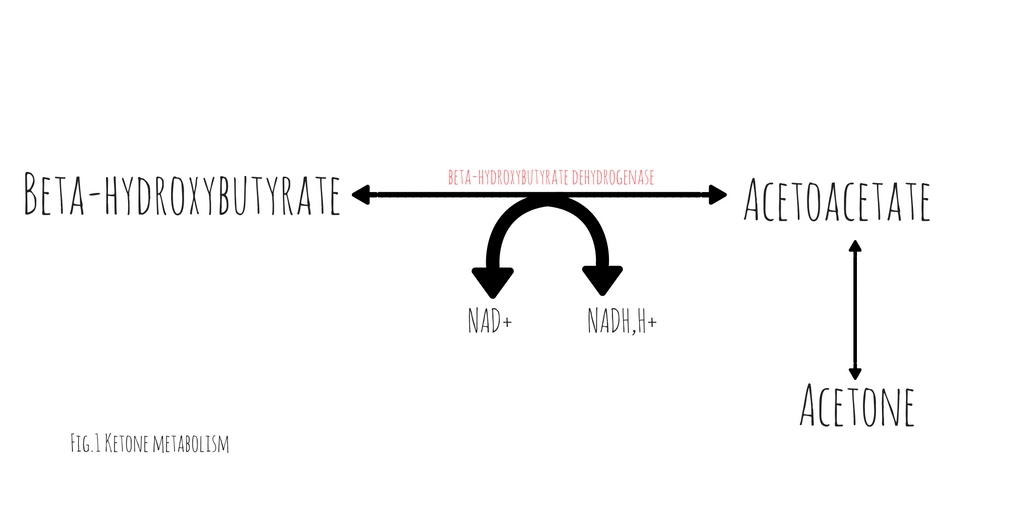

Is it possible to have a patient present in diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) with both negative serum and urinary ketone levels?

A case report published in American Journal of Emergency Medicine by Jehle et al provides a helpful reminder of this phenomenon (1). The degree of acidosis is directly related to the ratio of the various ketones/ketone metabolites: acetone, acetoacetate and beta-hydroxybutyrate present in the serum. The proportion of each respective substance is determined by the existing redox state in the blood. At any given time, acetoacetate and beta-hydroxybutyrate exist in an equilibrium dependent upon the ratio of NAD+ and NADH(fig.1). These substances freely convert with the assistance of the enzyme beta- hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase (2). This conversion requires the donation of a hydrogen atom from NADH. The balance between beta-hydroxybutyrate and acetoacetate, is determined by the ratio of NADH to NAD+. Acetoacetate will freely degrade into acetone through non-enzymatic decarboxylation. Early in DKA, acetoacetate is the most prevalent substance. As the disease progresses and the serum ratio of NADH to NAD+ increases, the proportion of beta-hydroxybutyrate rises, decreasing the quantity of acetoacetate and acetone.

hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase (2). This conversion requires the donation of a hydrogen atom from NADH. The balance between beta-hydroxybutyrate and acetoacetate, is determined by the ratio of NADH to NAD+. Acetoacetate will freely degrade into acetone through non-enzymatic decarboxylation. Early in DKA, acetoacetate is the most prevalent substance. As the disease progresses and the serum ratio of NADH to NAD+ increases, the proportion of beta-hydroxybutyrate rises, decreasing the quantity of acetoacetate and acetone.

Traditional serum and urinary ketone assays react strongly to acetoacetate but neither reliably react with beta-hydroxybutyrate. Patients in whom the majority of their anion gap is filled by beta-hydroxybutyrate, urinary or serum ketone levels may be negative. In such cases, serum beta-hydroxybutyrate assays would be positive but are not universally available.

It is important to note, with resuscitation and insulin therapy, the ratio of NADH/NAD+ will start to normalize causing an increase in the quantity of acetoacetate. As the patient improves and the anion gap clears, the degree of ketones detected in the serum and urine will paradoxically increase.

1. Jehle D, et al, Severe diabetic ketoacidosis presenting with negative serum ketones: First case report and a review of the mechanism, Am J Emerg Med (2016)

2. Konijn, Abraham M., Naama Carmel, and Nathan A. Kaufmann. The redox state and the concentration of ketone bodies in tissues of rats fed carbohydrate free diets. The Journal of nutrition 10 (1976): 1507.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: ROSC, Cardiac Arrest, ETCO2 (PubMed Search)

Posted: 8/2/2016 by Rory Spiegel, MD

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

Despite a lack of prospective data, end-tidal CO2 (ETCO2) is often proposed as a viable replacement for the traditional pulse check to identify return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) in patients presenting to the Emergency Department in Cardiac Arrest. A recent study by Tat et al examined this very question. The authors prospectively enrolled 178 patients suffering out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) and examined the accuracy of a rise in ETCO2 at predicting ROSC. The authors examined both a rise of 10 and 20 mm Hg in ETCO2. Of the 178 patients included in this cohort, 60 (34%) experienced ROSC. The sensitivity and specificity of ETCO2 to predict ROSC at a threshold of 10 mm Hg was 33% and 97% respectively. At a threshold of 20 mm Hg ETCO2 performed no better with a sensitivity and specificity of 20% and 99% respectively.

What this data suggests is while a rise of ETCO2 of greater than 10 is highly suggestive of ROSC, the contrary cannot be said. The absence of a spike in ETCO2 does not rule out ROSC, as the large majority of patients experiencing ROSC in this cohort did so without demonstrating a significant rise in ETCO2. This evidence suggests that ETCO2 is a poor surrogate for a pulse check.

Tat LC, Ming PK, Leung TK, Abrupt rise of end tidal carbon dioxide level was a specific but non sensitive marker of return of spontaneous circulation in patient with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, Resuscitation (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.04.018

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: CPR, Cardiac Arrest (PubMed Search)

Posted: 11/15/2016 by Rory Spiegel, MD

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

It is well documented that when left to our own respiratory devices we will consistently over-ventilate patients presenting in cardiac arrest (1). A simple and effective method of preventing these overzealous tendencies is the utilization of a ventilator in place of a BVM. The ventilator is not typically used during cardiac arrest resuscitation because the high peak-pressures generated when chest compressions are being performed cause the ventilator to terminate the breath prior to the delivery of the intended tidal volume. This can easily be overcome by turning the peak-pressure alarm to its maximum setting. A number of studies have demonstrated the feasibility of this technique, most recently a cohort in published in Resuscitation by Chalkias et al (2). The 2010 European Resuscitation Council guidelines recommend a volume control mode at 6-7 mL/kg and 10 breaths/minute (3).

1. Aufderheide TP, Sigurdsson G, Pirrallo RG, Yannopoulos D, McKnite S, von Briesen C, Sparks CW, Conrad CJ, Provo TA, Lurie KG. Hyperventilation-induced hypotension during cardiopulmonary resusci- tation. Circulation. 2004;109:1960 –1965.

2. Chalkias, Athanasios et al. Airway pressure and outcome of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A prospective observational study. Resuscitation. November 2016

3. Deakin CD, Nolan JP, Soar J, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010 Section 4. Adult advanced life support. Resuscitation 2010;81:1305–52.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: peri-Intubation, shock index (PubMed Search)

Posted: 2/7/2017 by Rory Spiegel, MD

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

Identifying patients at risk of hypotension during intubation is not always straight forward. The prevalence of peri-intubation hypotension in the Emergency Department has been demonstrated to be approximately 20%.1 And while certain variables increase the likelihood of peri-intubation hypotension (ex. Shock index> 0.80), no single factor predicts it accurately enough to be used at the bedside.2 In the majority of patients undergoing intubation, clinicians should be prepared for peri-intubation hypotension with either vasopressor infusions or push dose pressors.

1. Heffner AC, Swords D, Kline JA, Jones AE. The frequency and significance of postintubation hypotension during emergency airway management. J Crit Care. 2012;27(4):417.e9-13.

2. Heffner AC, Swords DS, Nussbaum ML, Kline JA, Jones AE. Predictors of the complication of postintubation hypotension during emergency airway management. J Crit Care. 2012;27(6):587-93.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: lung protective ventilation, ARDS (PubMed Search)

Posted: 3/21/2017 by Rory Spiegel, MD

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

While lung protective ventilatory strategies have long been accepted as vital to the management of patients undergoing mechanical ventilation, the translation of such practices to the Emergency Department is still limited and inconsistent.

Fuller et al employed a protocol ensuring lung-protective tidal volumes, appropriate setting of positive end-expiratory pressure, rapid weaning of FiO2, and elevating the head-of-bed. The authors found that the number of patients who had lung protective strategies employed in the Emergency Department increased from 46.0% to 76.7%. This increase in protective strategies was associated with a 7.1% decrease in the rate of pulmonary complications (ARDS and VACs), 14.5% vs 7.4%, and a 14.3% decrease in in-hospital mortality, 34.1% vs 19.6%.

Fuller BM, Ferguson IT, Mohr NM, et al. Lung-Protective Ventilation Initiated in the Emergency Department (LOV-ED): A Quasi-Experimental, Before-After Trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;

Category: Airway Management

Keywords: RSI, Preoxygenation (PubMed Search)

Posted: 9/13/2016 by Rory Spiegel, MD

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

During rapid sequence intubation (RSI) we endeavor to avoid positive pressure ventilation, prior to securing a definitive airway. As such, an adequate buffer of oxygen is necessary to ensure a safe apneic period. This process involves replacing the residual nitrogen in the lung with oxygen. It has been demonstrated that a standard nonrebreather (NRB) mask alone does not provide a high enough fractional concentration of oxygen (FiO2) to optimally denitrogenate the lungs (1). Even when a nasal cannula at 15L/min is utilized in addition to the NRB, the resulting FiO2 is not ideal. A bag-valve mask (BVM) with a one-way-valve or PEEP valve has been demonstrated to provide oxygen concentrations close to that of an anesthesia circuit. But its effectiveness is drastically reduced if a proper mask seal is not maintained during the entire pre-oxygenation period (1). This is not always logistically possible in the chaos of an Emergency Department intubation.

A standard NRB with the addition of flush-rate oxygen appears to be a viable alternative. Recently published in Annals of Emergency Medicine, Driver et al demonstrated that a NRB with wall oxygen flow rates increased to maximum levels, rather than the standard 15L/min, provided end-tidal O2 (ET-O2) levels similar to an anesthesia circuit (2).

1. Hayes-bradley C, Lewis A, Burns B, Miller M. Efficacy of Nasal Cannula Oxygen as a Preoxygenation Adjunct in Emergency Airway Management. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(2):174-80.

2. Driver BE, Prekker ME, Kornas RL, Cales EK, Reardon RF. Flush Rate Oxygen for Emergency Airway Preoxygenation. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;