Category: Critical Care

Posted: 10/21/2025 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Check for Elevated ICP in the Post-ROSC Patient

Long B, Gottlieb M. Emergency medicine updates: Managing the patient with return of spontaneous circulation. Am J Emerg Med. 2025; 26-36.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: delirium, ICU, acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (PubMed Search)

Posted: 10/14/2025 by Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

(Updated: 3/6/2026)

Click here to contact Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

Delirium is common among critically ill patients. Some of the common Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEI), rivastigmine, donepezil, have been used to prevent delirium in ICU patients. However, their efficacy was just recently re-examined in a meta-analysis of only Randomized Control Trials.

Ten studies and 731 patients were included- 365 in the treatment (AChEI) group and 366 in the control group.

AChEI was associated with lower occurrence of delirium (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.47-0.98, p=0.039. However, there was no significant difference in the delirium duration (mean difference -0.16 day, 95% CI -0.95 to 0.62 day, p=0.23). There was no difference in delirium severity nor length of hospital stay.

Among the medication, interestingly, rivastigmine 4.5 mg/day significantly reduced delirium occurrence (RR = 0.61 [0.39– 0.97]) and severity (SMD = –0.33 [–0.58 to –0.08]), as well as length of hospital stay (MD = –1.29 [–1.87 to –0.72]).

Discussion:

This meta-analysis was well-conducted.

The cholinergic dysregulation—especially elevated acetylcholinesterase activity—can lead to the imbalance between attention and cognition, contributing to delirium in ICU patients. Thus, the use of AChEI and reduction of occurrence of delirium proves that acetylcholine deficiency may be associated with delirium among ICU patients.

Subgroup analysis showed that prophylactic use of AChEI was associated with significant reduction of delirium duration. Thus, further studies are needed to define which populations will benefit from AChEI.

Conclusion:

AChEIs are effective in reducing occurrence of delirium, but they did not affect delirium duration, severity or hospital LOS.

Pipek LZ, Pascual GS, Nascimento RFV, Silva GD, Castro LH. Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors for Delirium Prevention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med. 2025 Oct 1;53(10):e2054-e2061. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000006786. Epub 2025 Aug 5. PMID: 40758382.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: acute respiratory failure, hypercapnia, hypercarbia, COPD, AE-COPD, noninvasive ventilation, high flow nasal cannula (PubMed Search)

Posted: 10/7/2025 by Kami Windsor, MD

Click here to contact Kami Windsor, MD

Q: Can you use high flow nasal cannula (HFNC) to manage acute hypercapnic respiratory failure?

A: It probably depends.

Background: While we now frequently utilize HFNC as an initial therapy for most acute hypoxic respiratory failure, its appropriateness in managing acute respiratory failure with hypercarbia has historically been opposed. With more recent data indicating that HFNC may be as good as noninvasive ventilation (NIV) for management of hypercapnia as well, this seemed like a good time to point out a few things:

The RENOVATE trial was a larger multicenter randomized noninferiority trial looking at HFNC vs NIV in all-comer acute respiratory failure, summarizing that HFNC was noninferior in the primary composite outcome of death + intubation at 7 days.

BUT this conclusion is not clearly supported in the smaller COPD (or acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema) subgroup:

What does seem to be clear across studies that HFNC has the capacity to clear some CO2 and is by and large better tolerated than facemask NIV.

Bottom Line: For mild-moderate acute COPD exacerbations with patient intolerance or exclusion criteria for NIV therapy, trialing HFNC is a reasonable option. For patients with severe acute or acute on chronic hypercapnia, as indicated by a [pseudo-arbitrary] pH < 7.25 and PaCO2 >70-80, noninvasive ventilation should be your go-to… or be ready to promptly intubate if/when the high flow fails.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: sepsis, septic shock, omeprazole, proton pump inhibitor, anti-inflammatory (PubMed Search)

Posted: 9/30/2025 by Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

Click here to contact Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

Settings: multinational, randomized, double- blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted in 17 centers in Italy, Russia, and Kazakhstan

Participants: A total of 307 ICU patients with sepsis or septic shock. Patients who were likely to die (APACHE II > 65 points) were excluded.

Treatment group: 80 mg bolus of omeprazole at randomization, at 12 hours and infusion of 12 mg/hour for 72 hours. Total dose of 1024 mg.

Outcome measurement: primary outcome of the study was organ dysfunction measured as the mean daily SOFA score during the first 10 days. Secondary outcomes were antibiotics-free days at 28 days; all-cause mortality at 28 days

Study Results:

Discussion:

Conclusion:

In sepsis patients, Esomeprazole did not re- duce organ dysfunction, despite demonstrating in vivo immunomodulatory effects

Monti G, Carta S, Kotani Y, Bruni A, Konkayeva M, Guarracino F, Yakovlev A, Cucciolini G, Shemetova M, Scapol S, Momesso E, Garofalo E, Brizzi G, Baldassarri R, Ajello S, Isirdi A, Meroi F, Baiardo Redaelli M, Boffa N, Votta CD, Borghi G, Montrucchio G, Rauch S, D'Amico F, Pace MC, Paternoster G, Vitale F, Giardina G, Labanca R, Lembo R, Marmiere M, Marzaroli M, Nakhnoukh C, Plumari V, Scandroglio AM, Scquizzato T, Sordoni S, Valsecchi D, Agrò FE, Finco G, Bove T, Corradi F, Likhvantsev V, Longhini F, Konkayev A, Landoni G, Bellomo R, Zangrillo A; PPI-SEPSIS Study Group. A Multinational Randomized Trial of Mega-Dose Esomeprazole as Anti-Inflammatory Agent in Sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2025 Aug 1;53(8):e1554-e1566. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000006720. Epub 2025 May 29. PMID: 40439536.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: compartment syndrome, abdomen, critically ill (PubMed Search)

Posted: 9/24/2025 by Robert Flint, MD

(Updated: 9/28/2025)

Click here to contact Robert Flint, MD

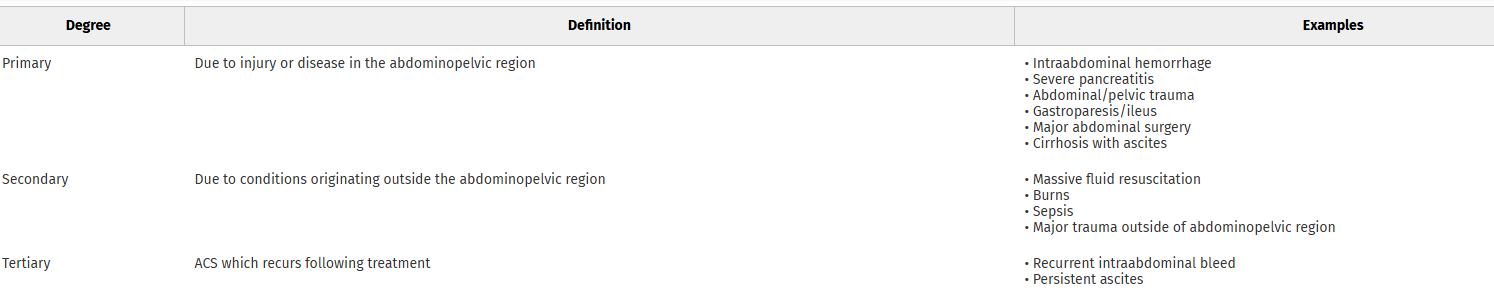

This review article reminds us that abdominal hypertension and compartment syndrome need to remain on our differential diagnosis for critically ill and injured patients. Pressure is measured with an intra-bladder catheter. Normal pressure is 5-7 mm HG. Sustained over 12 mm Hg is hypertension and sustained over 20 mm Hg is compartment syndrome.

Arcieri, Talia R. MD; Meizoso, Jonathan P. MD, MSPH, FACS. Intraabdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome: What you need to know. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 99(4):p 504-513, October 2025. | DOI: 10.1097/TA.0000000000004603

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Oxygenation, Lateral Positioning, Hypoxia (PubMed Search)

Posted: 9/9/2025 by Mark Sutherland, MD

(Updated: 3/6/2026)

Click here to contact Mark Sutherland, MD

We've got supine positioning and prone positioning... what about something in-between? Ye et al studied 2,159 patients coming out of anesthesia in a PACU after extubation. As sedation wore off, they placed one group in lateral decubitus, and left the other group supine. The lateral decubitus group had less hypoxia, a higher lowest SpO2, and required fewer airway rescue maneuvers.

Of note, the investigators didn't compare lateral or supine to prone positioning, which is often felt to be the best position for oxygenation (depending on patient characteristics and pathophysiology). And of course, this study represents a very specific scenario quite different from the ED (PACU patients post-extubation), so it's not clear how broadly extrapolatable this is. But this does add to the argument that supine is a poor position for oxygenating patients.

Bottom Line: If your supine patient is oxygenating marginally and you want a small bump without going all the way to prone positioning, consider lateral positioning. May make the most sense for procedural sedation and post-extubation patients in terms of similarity to this particular study.

Ye H, Chu LH, Xie GH, Hua YJ, Lou Y, Wang QH, Xu ZX, Tang MY, Wang BD, Hu HY, Ying J, Yu T, Wang HY, Wang Y, Ye ZJ, Bao XF, Wang MC, Chen LY, Wang XX, Zhang XB, Huang CS, Wang J, Lu YP, Luo FQ, Zhou W, Wang CG, Cheng H, Liu WJ, Luo J, Wu YQ, Li RR, Wang D, Hou LQ, Shi L, Zhang J, Wang K, Pi X, Zhou R, Yang QQ, Wan PL, Li H, Wu SJ, Song SW, Cui P, Shu L, Islam N, Fang XM. Effect of lateral versus supine positioning on hypoxaemia in sedated adults: multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2025 Aug 19;390:e084539. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2025-084539. PMID: 40829895; PMCID: PMC12362200.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Critical Care, oxygen, ventilator, SaO2 (PubMed Search)

Posted: 9/2/2025 by Zachary Wynne, MD

Click here to contact Zachary Wynne, MD

What is the ideal oxygen saturation goal for a mechanically ventilated patient? Literature over the past decade has led away from the perfect 100% oxygen saturation due to its association with worse patient outcomes across many disease states. It is theorized that excess oxygen leads to free radical production causing a lung injury pattern. However, there is no clear guidance for the ideal range of oxygen saturation goals, particularly in the mechanically ventilated patient, despite a meta-analysis and several recent trials.

UK-ROX Trial - JAMA - June 2025

Question: Does an oxygen saturation goal of 88-92% lead to a lower 90-day mortality compared to usual care?

Population: 16,500 mechanically ventilated adult patients in 97 ICU’s across the UK, excluded patients on ECMO

Intervention: Goal oxygen saturation of 88-92%, using the lowest possible FiO2

Control: Usual care, defined as oxygen supplementation at the discretion of the treating physician (no limits set to FiO2 or SaO2)

Outcomes:

Bottom Line:

Ideal oxygenation targets remain elusive. UK-ROX adds to the growing literature of oxygenation targets in mechanically ventilated patients but does not clearly show that lower oxygen saturation targets lead to improved ICU outcomes. In your emergency department ICU boarder, avoid a 100% oxygen saturation to prevent oxygen toxicity associated lung injury and consider an oxygen saturation goal of 90-96% (88-92% if history of COPD).

Martin DS, Gould DW, Shahid T, Doidge JC, Cowden A, Sadique Z, Camsooksai J, Charles WN, Davey M, Francis-Johnson A, Garrett RM, Grocott MPW, Jones J, Lampro L, Mackle DM, O'Driscoll BR, Richards-Belle A, Rostron AJ, Szakmány T, Warren A, Young PJ, Rowan KM, Harrison DA, Mouncey PR; UK-ROX Investigators. Conservative Oxygen Therapy in Mechanically Ventilated Critically Ill Adult Patients: The UK-ROX Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2025 Aug 5;334(5):398-408. doi: 10.1001/jama.2025.9663. PMID: 40501321; PMCID: PMC12163715.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: hyperbaric, dive medicine, evaluation, (PubMed Search)

Posted: 8/31/2025 by TJ Gregory, MD

(Updated: 3/6/2026)

Click here to contact TJ Gregory, MD

You've encountered it at ABEM General Hospital, but now a SCUBA diver actually comes into your ED and you're concerned for DCS. What next?

Evaluation:

Symptom nature and timing are key in detailed history. Transient neurocognitive symptoms at depth suggest nitrogen narcosis or oxygen toxicity. Neurological symptoms within 10 minutes of surfacing suggest AGE. Widely variable symptoms within 24 hours of surfacing suggest DCS. Symptom onset greater than 24 hours suggests alternative diagnosis (still discuss with Hyperbaric Medicine or DAN).

Thorough physical exam. DCS may manifest only as localized pain. Look for marine envenomation or trauma to the area.

Neurological exam including detailed sensation and ataxia/balance - get the patient on their feet!

Unbiased differential. E.g. DCS may cause chest pain or SOB, but divers still have heart attacks. SCUBA setting may raise alert for AGE, but divers still have strokes. People go to the tropics to dive, but they also eat local fish (Scombroid and Ciguatera for a future pearl).

Management:

Early consult to Hyperbaric Medicine. In settings with no such team available, a good resource is the Divers Alert Network (DAN) Emergency Hotline at 1-919-684-9111

100% O2 via NRB or highest available delivery. You're not titrating to spO2, you're creating a diffusion gradient for tissue inert gas washout.

IV access and isotonic Fluids. PO if tolerable and unable to obtain IV access.

NSAIDs unless otherwise contraindicated. No special regimen. Standard dosing Ibuprofen or Naproxen are fine. Toradol is ok if limitations to PO.

Horizontal positioning in bed for AGE. Trendelenburg is not recommended.

Manage end organ effects as applicable. E.g. Spinal DCS may yield bladder retention requiring foley

Give consideration to activity specific considerations: hypothermia, restrictive clothing, etc

IV lidocaine has mixed evidence for neuroprotection in AGE. Discuss with Hyperbaricist before starting.

Pre-hospital considerations:

Transport should occur via ground or pressurized air transit capable of 1.0 ATA (sea level) cabin pressure. If non-pressurized aircraft transport is absolutely necessary, maintain continuous oxygen supplementation and altitude less than 2000 feet. This also applies to the inter-hospital setting.

O2 delivery by best means available to include SCUBA regulator mouthpiece or even a rebreather apparatus if present.

PO fluids if tolerable and no IV available.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8378877/

[Clinical aspects, pathophysiology and therapy of decompression sickness]Abstract The primary treatment of decompression illnesses (arterial gas embolism and all types of decompression sickness) is recompression therapy, combined with hyperbaric oxygen breathing. It is essential to initiate treatment as soon as the symptoms arise. However, prior to hyperbaric oxygen therapy--particularly with any delay in starting recompression--specific supportive therapy for ...pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Decompression Sickness - Injuries; Poisoning - MSD Manual Professional Edition

Decompression Sickness - MSD ManualsSymptoms and Signs of Decompression Sickness Severe symptoms may manifest within minutes of surfacing, but in most patients, symptoms begin gradually, sometimes with a prodrome of malaise, fatigue, anorexia, and headache. Symptoms occur within 1 hour of surfacing in approximately 50% of patients and by 6 hours in 90%. Rarely, symptoms can manifest 24 to 48 hours after surfacing, particularly ...www.msdmanuals.com

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 8/26/2025 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

(Updated: 3/6/2026)

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Predicting NIV Failure

Frat JP, et al. Noninvasive respiratory supports in the ICU. Intensive Care Med. 2025; 51:1476-89.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: vasopressors, vasopressin, septic shock (PubMed Search)

Posted: 8/18/2025 by Jessica Downing, MD

(Updated: 8/19/2025)

Click here to contact Jessica Downing, MD

Norepinephrine (NE) is widely accepted as the first-line vasopressor for the management of septic shock, supported by the Surviving Sepsis Guidelines (1). The use of vasopressin as a second-line agent is also supported by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign, although the appropriate “triggers” for its addition remain vague. The SSG recommend adding vasopressin when NE infusion rates reach 0.25-0.6 mcg/kg/min, citing a catecholamine-sparing effect and potentially improved mortality (1, 2, 3).

What’s New?

The OVISS study (“Optimal vasopressin initiation in septic shock. The OVISS reinforcement learning study”) used machine learning to derive and internally validate a set of rules guiding the addition of vasopressin to NE for patients with septic shock using multiple databases of patient encounters across multiple institutions (4).

The machine learning model suggested initiation of vasopressin in more patients (87% vs 31%), earlier, and in less sick patients than was seen to be common practice:

Practice consistent with the above triggers was associated with decreased odds of in-hospital mortality (AOR 0.81, 95% CI 0.73-0.91).

Limitations

This was not a prospective study or RCT and was only internally validated. Using databases may limit the number of clinical variables available for analysis, and clinical judgment (how the patient looks) is not reflected.

Bottom Line

Consider adding vasopressin for patients with vasodilatory shock with low MAP despite NE >0.2mcg/kg/min and adequate fluid resuscitation, though more evidence is needed for a strong recommendation. As dual-pressor therapy may be riskier via peripheral IV and vasopressin does not have a direct antidote for extravasation, consider central line placement when adding vasopressin (5,6)

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: intubation, sedation, rapid sequence intubation, RSI, rocuronium, succinylcholine, etomidate, ketamine, propofol (PubMed Search)

Posted: 8/12/2025 by Kami Windsor, MD

Click here to contact Kami Windsor, MD

Whether you agree or disagree that “roc rocks and succ sucks,” evidence shows that approximately 3-4% of intubated patients experience awareness while paralyzed [1,2], and more of these patients are in the rocuronium subgroup [2,3,4]. Rocuronium acts in a dose-dependent fashion; the relatively standard 1-1.2 mg/kg in emergency department rapid sequence intubation (RSI) can result in a duration of paralysis can of up to 60-90 minutes. Commonly used sedatives in RSI, however, such as etomidate and ketamine, wear off quickly, before before rocuronium's paralytic effects have abated.

A recent single-center study showed that the majority of patients (60%) receiving rocuronium for paralysis during rapid sequence intubation (RSI) received no additional sedation until more than 15 minutes after induction, whether in the ED or ICU [5].

Patients experiencing awareness during paralysis with post-traumatic stress disorder [1,2] including distress from being restrained, feeling procedures, and feeling of impending death.

Bottom line: Start appropriate dose sedation promptly after RSI, especially with rocuronium, to avoid short- and long-term distress to patients.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: diarrhea, ICU, mechanically ventilated (PubMed Search)

Posted: 8/4/2025 by Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

Click here to contact Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

Have you ever wondered what happened to your mechanically ventilated patients who developed diarrhea. Apparently, a multicenter study involving 2650 patients from 44 ICUs in the US, Canada and Saudi Arabia investigated the prevalence of diarrhea among these patients.

This study was the Editor’s choice for June 2025.

Results:

The mean age for the population was 59.8 (16.5) years, with APACHE II Score of 22.0 (7.8). Up to 61% of the patients received vasopressors or inotropes on day 1, which mean these patients are relatively ill.

Up to 60% of patients had diarrhea during their ICU stay, with 15% had diarrhea on day 1 or 2.

Initiating laxatives and antibiotics (who in the ICU would not receive vitamin V and Vitamin Z?) were associated with increased risk of diarrhea: HR for laxatives 1.28 (1.13–1.44), p<0.001; HR for antibiotics 1.41 (1.20–1.67), P< 0.001.

Furthermore, enteral feeding with high/moderate protein concentration was also associated with diarrhea (HR 1.13, 1.00-1.28, P=0.045.

Not surprisingly, diarrhea was associated with higher number of C. Diff testing.

Although patients with diarrhea were associated with longer ICU stay (15 [10-23] days) vs. those without diarrhea (8 [6-12] days), it was not associated with higher mortality (HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.57-0.86, P<0.001)

Discussion:

1. The authors did not report the rates of positive C. Diff. infection in these patients during ICU stay, although they did report that for another study in this population, the rate of positive C. Diff. infection during ICU stay was 2.2%. If only 2.2% had C. Diff. infection while up to 60% had diarrhea. Consequently, for every 30 patients with diarrhea, only one patient had C. Diff. infection. Therefore, do we have to check C. Diff. in those ICU patients with diarrhea every time?

2. The authors hypothesized that patients with diarrhea had longer ICU stay and lower mortality because they survived long enough to develop diarrhea. Thus, diarrhea is bad for clinicians, but may not be too bad for patients?

Conclusion:

Diarrhea is common among invasively ventilated patients. Patients who received laxatives, antibiotics, enteral feeding with high protein amount are at higher risk for diarrhea.

Dionne JC, Johnstone J, Heels-Ansdell D, Tahvildar Khazaneh P, Zytaruk N, Clarke F, Hand L, Millen T, Dechert W, Porteous R, Auld F, Hunt M, Campbell E, Bentall T, Campbell T, Smith O, Rose L, Arabi YM, Duan E, Wilcox ME, McIntyre L, Rochwerg B, Karachi T, Adhikari NK, Charbonney E, St-Arnaud C, Kristof A, Khwaja K, Marquis F, Zarychanski R, Golan E, Cook D; PROSPECT Research Coordinators Group, the PROSPECT Investigators and the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Diarrhea in Mechanically Ventilated Patients: A Nested Multicenter Substudy. Crit Care Med. 2025 Jun 1;53(6):e1247-e1256. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000006667. Epub 2025 Apr 3. PMID: 40459385.

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 7/29/2025 by Caleb Chan, MD

Click here to contact Caleb Chan, MD

PEEP is often titrated up along with FiO2 to increase oxygen saturation. Although the potential negative hemodynamic effect of high PEEP is often recognized, it is important to also note that high PEEP can also paradoxically worsen oxygen saturation.

The primary physiologic explanation for this phenomenon in a patient with pulmonary disease is due to the varying impact of PEEP on the intra- vs. extra-alveolar blood vessels. PEEP preferentially distends more normal/compliant lung which causes compression of intra-alveolar vessel at excessively high levels of PEEP. This causes pulmonary blood to be diverted to areas of lower vascular resistance (e.g. consolidated lung which is less distended due to its worsened compliance) and lower VQ matching. Essentially, blood flow to normal/healthy lung is decreased and is instead increased to diseased lung, worsening hypoxemia.

Bottom line:

High PEEP can potentially worsen hypoxemia and should be considered as an etiology for worsening oxygen saturation, particularly when the hypoxemia is out of proportion to the patient’s radiographic findings.

Çoruh B, Luks AM. Positive end-expiratory pressure. When more may not be better. Annals ATS. 2014;11(8):1327-1331.

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 7/23/2025 by William Teeter, MD

Click here to contact William Teeter, MD

Secondary analysis of a multicenter, prospective, observational study ICE-CRASH study in Japan including adult patients admitted with moderate-to-severe accidental hypothermia between 2019 and 2022.

Some structural generalizability (median age 81 years!) issues with this study but well done overall.

Authors undertook some rather complex modeling to predict outcomes related to rapid rewarming, showing that “the rewarming rate and predicted probability of each outcome increased significantly up to 3°C/hr, but when the rewarming rate exceeded 3°C/hr, the predicted probability of each outcome was almost constant.”

Suggests that for those with severe hypothermia that an initially rapid rate of up to 3C/hr is a good target for a ceiling, but above this may be associated with less favorable risk:benefit ratio. Benefit in moderate hypothermia was not as clear.

Conclusion: The mode of rewarming in severe hypothermia should still be based on local protocols and capabilities (e.g. external, intravascular, extracorporeal rewarming) but the rate of rewarming up to 3C/hr is associated with better outcomes.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Hypotension, Shock, Mean Arterial Pressure, Vasopressors, Elderly Patients, Geriatrics (PubMed Search)

Posted: 7/15/2025 by Mark Sutherland, MD

Click here to contact Mark Sutherland, MD

Following up Dr. Flint's pearl from the other day, the largest study to date looking at a lower Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) target in elderly ICU patients is the “65” Trial, published in JAMA in 2020. This trial compared a MAP target of 60-65 to the usual goal of >65, in critically ill patients age 65 and older. It included 2,455 patients in 65 ICUs in the UK, and found no difference between the groups.

Bottom Line: Although most intensivists still target a MAP > 65 regardless of patient age, you do have some evidence to support you if you want to target 60-65 in patients over age sixty-five. However, there are some important limitations (well outlined in the PulmCrit article linked below), and therapy should always be optimized to the patient and markers of end organ perfusion.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Sedation, propofol, dexmedetomidine, RASS (PubMed Search)

Posted: 7/8/2025 by Zachary Wynne, MD

Click here to contact Zachary Wynne, MD

The presence of an endotracheal tube by itself does not mandate sedation and many patients require no sedatives while intubated in the ICU. However, patients intubated in the emergency department usually require initial sedation while still paralyzed from RSI. Sedation can also help facilitate procedures and imaging in critically ill patients during initial management.

Current literature has found increased mortality and length of ventilator requirement in oversedated ED patients. The target sedation level for the general population remains a goal RASS (Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale) of 0 to -1. Society of Critical Care Medicine guidelines from early 2025 recommend dexmedetomidine over propofol as the preferred sedative for light sedation and reducing delirium risk in intubated critically ill patients. A recent trial re-examined other clinical outcomes between these two common sedative agents.

A2B Randomized Clinical Trial - JAMA 2025

Clinical Question: Does alpha 2 adrenergic receptor agonist sedation (dexmedetomidine or clonidine) reduce duration of mechanical ventilation in mechanically ventilated patients compared to a propofol based regimen (usual care)?

Where: 41 UK ICU’s from December 2018 to October 2023

Who: 1438 adults receiving mechanical ventilation for less than 48 hours, receiving propofol and opioid for sedation/analgesia, expected to require mechanical ventilation for greater than 48 hours

Intervention: protocol driven sedation to reach a RASS score of -2 to +1 (either dexmedetomidine, clonidine, or propofol). Of note, propofol could be added to achieve deeper sedation goal if deemed necessary by care team.

Outcomes:

Bottom Line:

While either dexmedetomidine or propofol, with appropriate use of opiates for pain management, are appropriate agents in non-paralyzed mechanically-ventilated patients, propofol may be a more appropriate choice in patients with greater agitation while boarding in the emergency department. However, close attention is needed to avoid the overly deep analgosedation associated with increased mortality. Maintain a goal RASS of 0 to -1 with frequent re-evaluation of your ICU boarders.

Walsh TS, Parker RA, Aitken LM, McKenzie CA, Emerson L, Boyd J, Macdonald A, Beveridge G, Giddings A, Hope D, Irvine S, Tuck S, Lone NI, Kydonaki K, Norrie J, Brealey D, Antcliffe D, Reay M, Williams A, Bewley J, Creagh-Brown B, McAuley DF, Dark P, Wise MP, Gordon AC, Perkins GD, Reade MC, Blackwood B, MacLullich A, Glen R, Page VJ, Weir CJ; A2B Trial Investigators. Dexmedetomidine- or Clonidine-Based Sedation Compared With Propofol in Critically Ill Patients: The A2B Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2025 Jul 1;334(1):32-45. doi: 10.1001/jama.2025.7200. PMID: 40388916; PMCID: PMC12090071.

Lewis K, Balas MC, Stollings JL, et al. A focused update to the clinical practice guideline for the prevention and management of pain, anxiety, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption in adult patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2025 Mar 1;53(3):e711-e727.

Stephens RJ, Ablordeppey E, Drewry AM, Palmer C, Wessman BT, Mohr NM, Roberts BW, Liang SY, Kollef MH, Fuller BM. Analgosedation Practices and the Impact of Sedation Depth on Clinical Outcomes Among Patients Requiring Mechanical Ventilation in the ED: A Cohort Study. Chest. 2017 Nov;152(5):963-971. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.05.041. Epub 2017 Jun 21. PMID: 28645462; PMCID: PMC5812748.

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 7/1/2025 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

(Updated: 3/6/2026)

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

When To Initiate RRT in the Critically Ill Patient

Barbar SD, Wald R, Quenot JP. Acute kidney injury: when and how to start renal replacement therapy. Intensive Care Med. 2025;51:1172-1175.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: ventilation ineffective-trigger double-trigger (PubMed Search)

Posted: 6/24/2025 by Cody Couperus-Mashewske, MD

Click here to contact Cody Couperus-Mashewske, MD

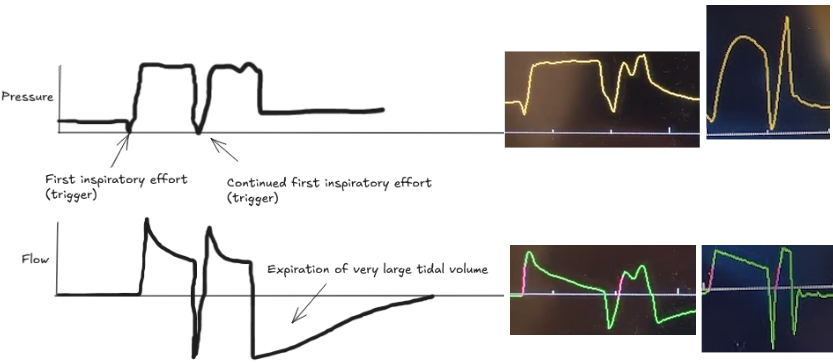

Patient-ventilator dyssynchrony is a sign of a disagreement between the patient's breathing and the ventilator's settings. Recognizing and fixing it is a critical skill to prevent lung injury and improve comfort. Ineffective triggering and double-trigger are two common types of dyssynchrony.

The patient tries to take a breath, but they are too weak to trigger the ventilator. This is the most common type of dyssynchrony. It causes increased work of breathing and discomfort.

Look for a small dip in the pressure waveform and a simultaneous scoop out of the expiratory flow waveform that is not followed by a delivered breath.

Troubleshooting options:

The patient's own breath outlasts the ventilator's set inspiratory time (Ti), causing one patient effort to trigger two stacked breaths. This results in delivery of large tidal volumes, risking lung injury (volutrauma).

Look for two consecutive breaths on the ventilator screen without a full exhalation in between.

Troubleshooting options:

Dyssynchrony means the ventilator settings do not match the patient's needs. Watch the waveforms to diagnose the mismatch, then either adjust the ventilator or treat the underlying problem.

Thille, A. W., Rodriguez, P., Cabello, B., Lellouche, F., & Brochard, L. (2006). Patient-ventilator asynchrony during assisted mechanical ventilation. Intensive care medicine, 32, 1515-1522.

Blanch, L., Villagra, A., Sales, B., Montanya, J., Lucangelo, U., Luján, M., ... & Kacmarek, R. M. (2015). Asynchronies during mechanical ventilation are associated with mortality. Intensive care medicine, 41, 633-641.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: ARDS (PubMed Search)

Posted: 6/16/2025 by Jordan Parker, MD

(Updated: 6/17/2025)

Click here to contact Jordan Parker, MD

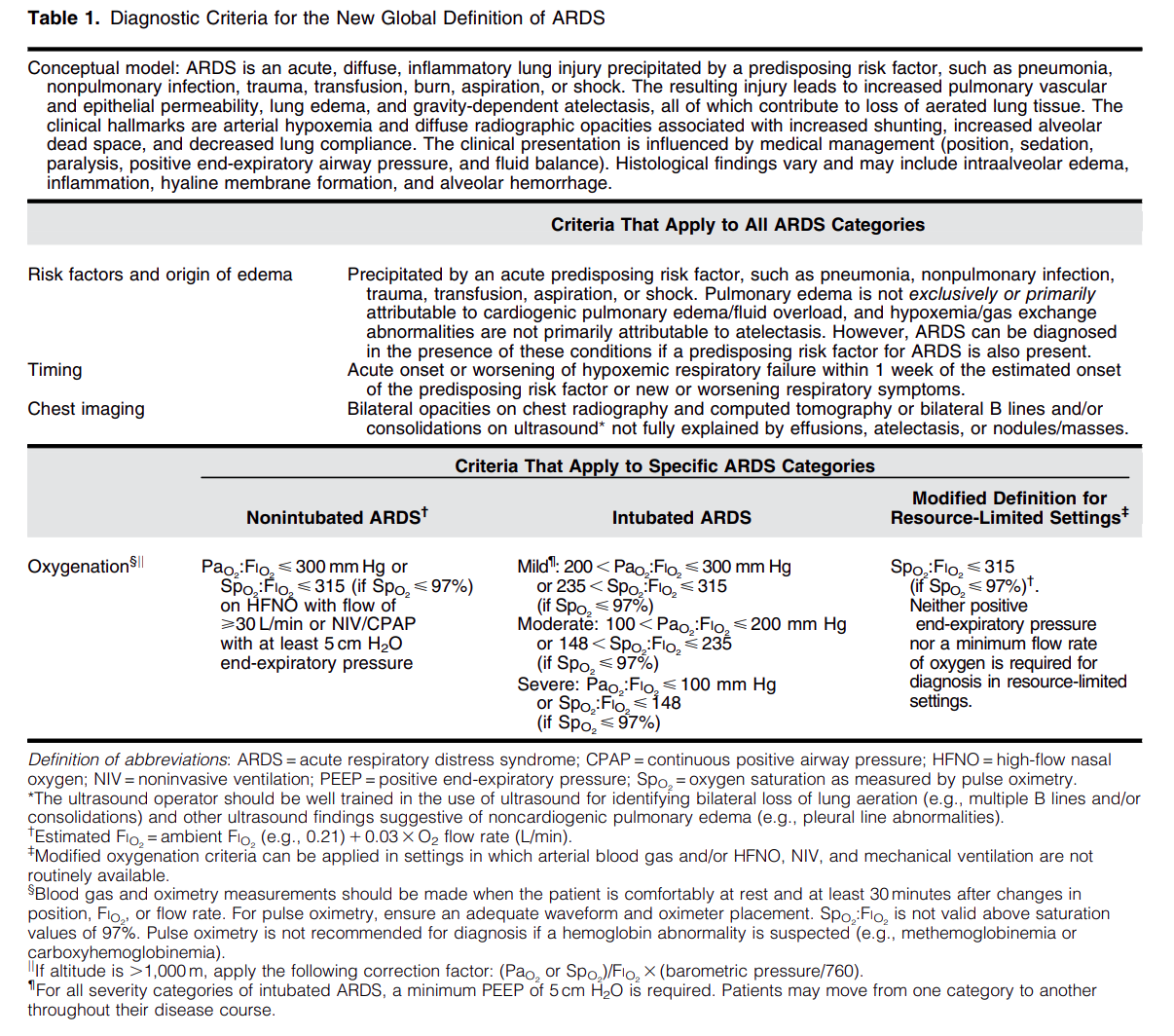

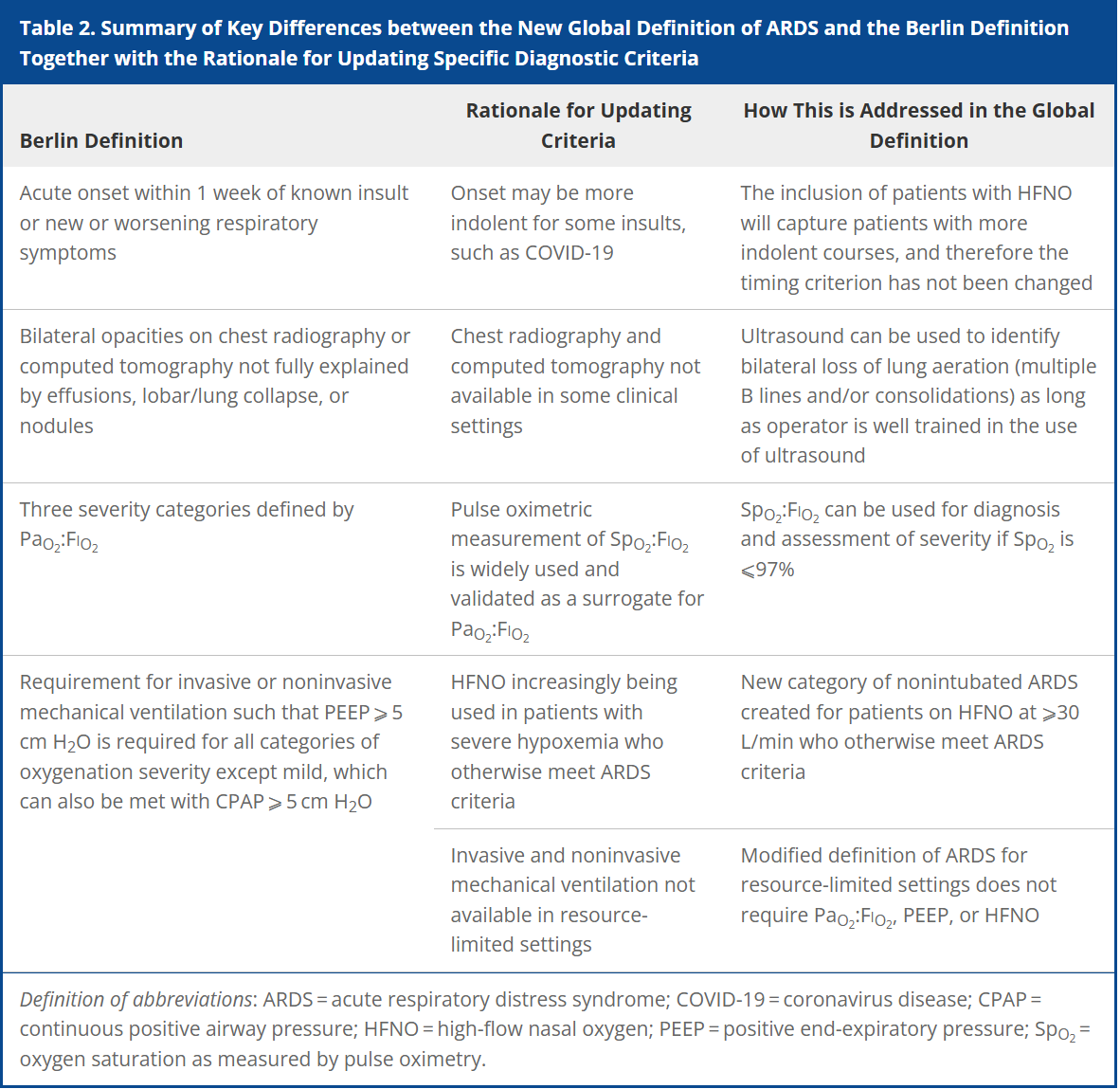

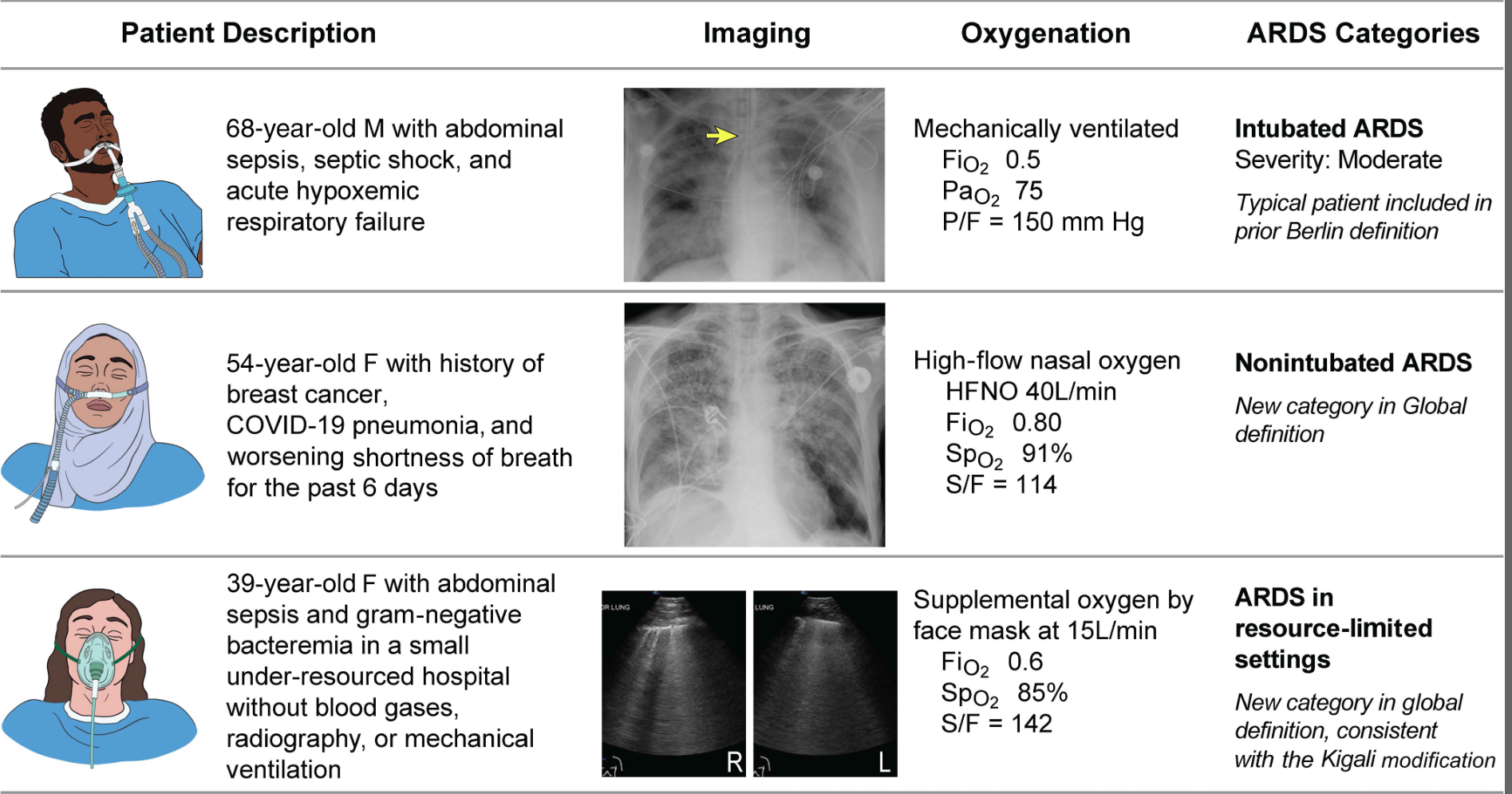

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is an acute, inflammatory lung injury that effects the lung diffusely and can be triggered by various insults. Aside from the Kigali modification, the most recent updated definition of ARDS was the Berlin definition in 2012. There have been many advances and changes in the understanding and clinical practice for managing patients with ARDS since then. In 2024, Matthay, et al. proposed the new global definition to build upon the Berlin criteria [1]. They addressed several important issues with the Berlin definition to improve the diagnostic criteria and improve ability for diagnosis in resource-limited settings.

ARDS Berlin Definition

Important updates for the Global definition of ARDS

Diagnostic Criteria for the New Global Definition of ARDS from Matthay et al.

The Global Definition of ARDS expands upon the Berlin definition. It was shown that this new definition improves diagnosis in resource-limited settings, allows for earlier detection, and better classification [2]. A retrospective study evaluating this new global definition found that there was a significant number of patients identified using this new definition who would have been missed using the Berlin definition [3]. These patients may benefit from ARDS directed therapies and further prospective studies will be needed to assess how this new definition effects clinical management of these patients using the new definition.

Helpful table/figure from the paper.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Cardiac Arrest, PEA, ROSC (PubMed Search)

Posted: 6/9/2025 by Harry Flaster, MD

Click here to contact Harry Flaster, MD

Pulse Checks in Cardiac Arrest: Your Fingers Are Not Reliable.

Summary: Whenever possible, use an ultrasound or an arterial line for pulse checks. Our fingers are not reliable.

Key points:

Multiple studies have demonstrated that manual pulse checks are not a reliable method to determine ROSC. Arterial lines and ultrasound are far more reliable methods. However, using more accurate measures of circulation lead to an additional dilemma: at what MAP, SBP, or ultrasound measured flow should we stop chest compressions? There is no agreed upon number, and as with most dilemmas in clinical medicine, the best answer is, “it depends”. However, a MAP > 50 or SBP > 60 for most patients is a reasonable choice to stop chest compressions. MAP < 50 or SBP < 60 are unlikely to provide adequate perfusion to the brain, and chest compressions should be resumed.

References: