Category: Critical Care

Keywords: CPR, Cardiac Arrest (PubMed Search)

Posted: 11/15/2016 by Rory Spiegel, MD

(Updated: 2/1/2026)

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

It is well documented that when left to our own respiratory devices we will consistently over-ventilate patients presenting in cardiac arrest (1). A simple and effective method of preventing these overzealous tendencies is the utilization of a ventilator in place of a BVM. The ventilator is not typically used during cardiac arrest resuscitation because the high peak-pressures generated when chest compressions are being performed cause the ventilator to terminate the breath prior to the delivery of the intended tidal volume. This can easily be overcome by turning the peak-pressure alarm to its maximum setting. A number of studies have demonstrated the feasibility of this technique, most recently a cohort in published in Resuscitation by Chalkias et al (2). The 2010 European Resuscitation Council guidelines recommend a volume control mode targeting tidal volumes of 6-7 mL/kg and a respiratory rate of 10 breaths/minute (3).

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 11/8/2016 by Daniel Haase, MD

Click here to contact Daniel Haase, MD

It's Election Day in the US, so here are some interesting facts about Presidential causes of death:

George Washington likely died from epiglottitis on 12/14/1799

CLICK BELOW FOR MORE INTERESTING FACTS!

Other interesting facts:

Leading causes of death:

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 11/1/2016 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Dynamic LVOT Obstruction

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: US, right ventricle, heart failure (PubMed Search)

Posted: 10/25/2016 by Rory Spiegel, MD

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

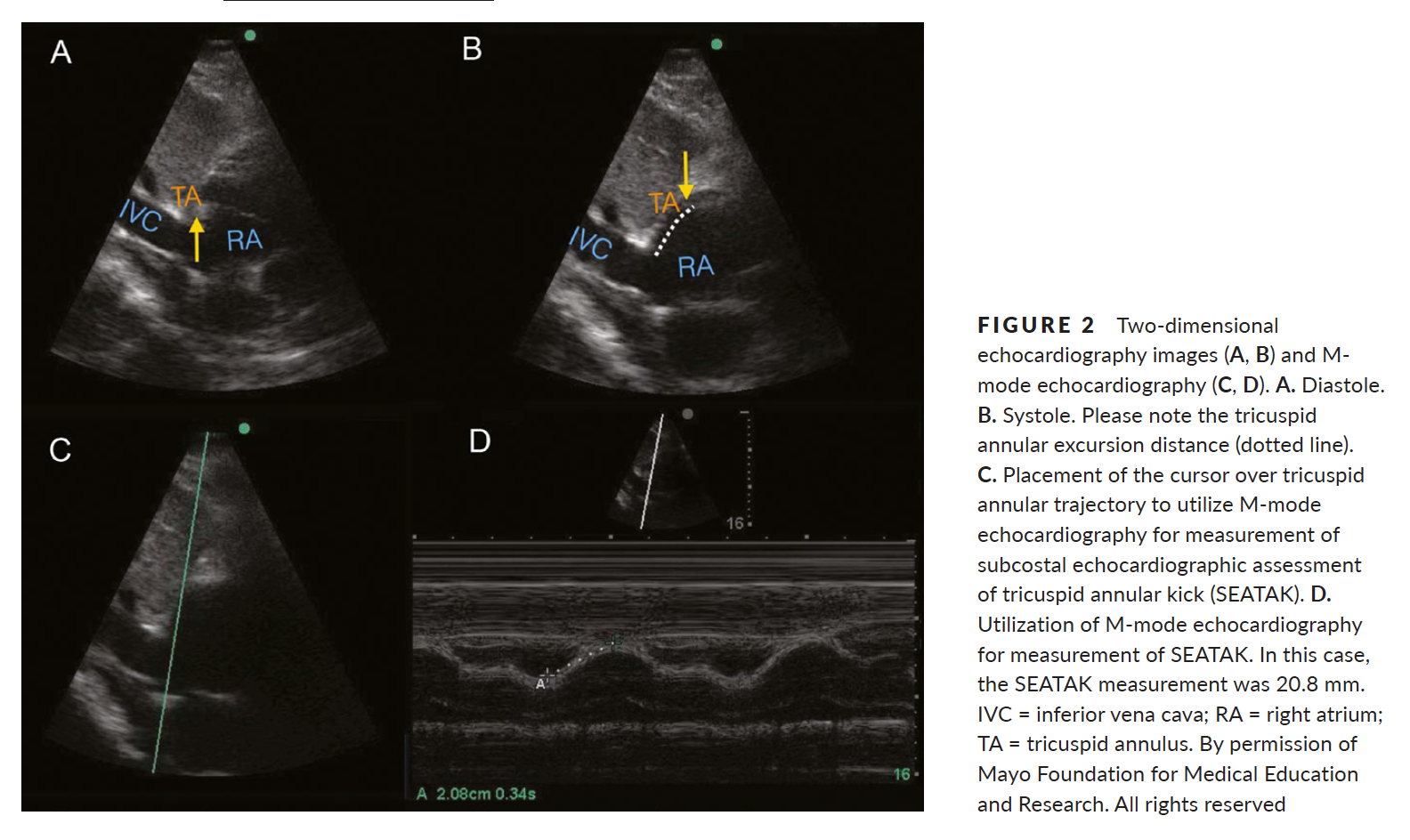

Recently Emergency Physicians have become far more aware of the importance of right ventricular (RV) function in our critically ill patient population. One of the methods that has been proposed to assess RV systolic function with bedside ultrasound (US) is the tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE). This simple bedside measurement utilizes M-mode to quantify the movement of the tricuspid annulus in systole. And while it has demonstrated reasonable accuracy at predicting RV dysfunction, adequate visualization of the lateral tricuspid annulus is not always obtainable in our critically ill patient population (1,2). In these circumstances an alternative measurement obtained in the subcostal window may be a viable option.

Similar to TAPSE, subcostal echocardiographic assessment of tricuspid annular kick (SEATAK) utilizes M-mode to assess the apical movement of the tricuspid annulus during systole. In a recent prospective observational study, Díaz-Gómez et al examined 45 ICU patients, 20 with known RV dysfunction and 25 with normal function. They compared the measurements obtained from TAPSE and SEATAK and found a strong correlation between the two measurement (Spearman’s ρ coefficient of .86, P=.03).

The small sample size and limited evaluation of RV function is far from ideal and more robust data sets are required before we cite SEATAK’s diagnostic accuracy with any confidence, but in the subset of patients where a TAPSE is unobtainable this may serve as an adequate surrogate until a more thorough echographic assessment can be obtained.

1. Ueti OM, Camargo EE, Ueti Ade A, et al. Assessment of right ventricular function with Doppler echocardiographic indices derived from tricuspid annular motion: comparison with radionuclide angiography. Heart. 2002;88:244–248.

2. Díaz-Gómez, J. L., Alvarez, A. B., Danaraj, J. J. , Freeman, M. L., Lee, A. S., Mookadam, F., Shapiro, B. P. and Ramakrishna, H. (2016), A novel semiquantitative assessment of right ventricular systolic function with a modified subcostal echocardiographic view. Echocardiography, 00: 1–9. doi: 10.1111/echo.13400.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: ECMO, PE, hypotension (PubMed Search)

Posted: 10/18/2016 by Daniel Haase, MD

(Updated: 4/10/2018)

Click here to contact Daniel Haase, MD

--Massive PE is defined as PE with obstructive shock (hypotension [SBP <90] or end-organ malperfusion)

--Consider venoarterial (VA) ECMO in massive PE for hemodynamic support, particularly prior to intubation

--VA ECMO may prevent intubation/mechanical ventilation, surgical intervention, systemic and local thrombolysis

--Patients on VA ECMO require systemic anti-coagulation to prevent arterial embolism. So, patients with relative and absolute contraindications to catheter-directed and systemic thrombolysis should be considered for VA ECMO for HD support while AC works.

--Intubating already hemodynamically tenuous patients is dangerous and increases in intra-thoracic pressure worsens RV failure and suppressing patient's catecholamine drive with sedation during RSI may also worsen hemodynamics.

--Frequently, patients who get VA ECMO will not require surgical embolectomy as the clot burden will resolve after a few days of heparin. And RV function with improve as demonstrated by serial echocardiography

--A recent review showed an overall survival of 70% in VA ECMO patients for massive PE. This included patients already in cardiac arrest. Review included case series, cohorts, but no RCTs.

1. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in acute massive pulmonary embolism: a systematic review. Yusuff HO, Zochios V, Vuylsteke A. Perfusion. 2015 Nov;30(8):611-6. doi: 10.1177/0267659115583377. Epub 2015 Apr 24. Review.

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 10/11/2016 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

(Updated: 2/1/2026)

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Oxygen-ICU Trial

A few additional important points about this particular study should be emphasized:

Girardis M, et al. Effect of conservative vs conventional oxygen therapy on mortality among patients in an intensive care unit. The Oxygen-ICU randomized trial. JAMA 2016. [epub ahead of print]

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Acid-base, SID, Delta Gap (PubMed Search)

Posted: 10/4/2016 by Rory Spiegel, MD

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

The delta gap is a measurement intended to assess for mixed acid-base disorders. A straightforward alternative, the strong ion difference (SID), allows for a quick and simple assessment of any non-gap acidosis or alkalosis that may be present.

The SID is simply the difference between the strong cations (Na+, K+, Mg+, Ca+) and the strong anions (Cl-) present in the serum. The abbreviated SID is the difference between the serum sodium and serum chloride levels (approximately 138-102). Values typically range from 36-40 mg/dl. Values less than 36 denote the presence of some degree of hyperchloremic, non-gap, acidosis. While values greater than 40 demonstrate the presence of hypochloremic, non-gap, alkalosis. And while on rare occasions, variations in albumin or elevated levels of cations other than sodium can lead you astray, the SID is as accurate as a delta gap at identifying mixed acid-based disorders without the added mathematical complexity.

Story DA. Stewart Acid-Base: A Simplified Bedside Approach. Anesth Analg. 2016;123(2):511-5.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Fluids, Fluid resuscitation, Metabolic Acidosis (PubMed Search)

Posted: 9/27/2016 by Daniel Haase, MD

Click here to contact Daniel Haase, MD

TAKE HOME POINTS:

-- High chloride load is associated with adverse outcomes in large-volume resuscitation (>60mL/kg in 24h), including increased risk of death [1]

-- Avoid supraphysiologic chloride solutions (i.e. normal saline) when resuscitation volumes are likely to exceed 60mL/kg (e.g. sepsis, DKA)

-- Hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis (HMA) is frequently associated with large-volume resuscitation, particularly with normal saline (0.9% NS) [2]

--HMA can result in decreased renal blood flow and renal cortical hypoperfusion, even in healthy volunteers [3]

-- Chloride load is also associated with acute kidney injury in this study, but this effect goes away once severity of illness is controlled.

-- It is not clear why increased chloride load is associated with increased mortality

-- Consider more "physiologic" fluids, such as plasmalyte A

1. Sen A, Keener CM, et al. Chloride Content of Fluids Used for Large-Volume Resuscitation Is Associated With Reduced Survival. Crit Care Med. 2016 Sep 15. [Epub ahead of print]

2. Kellum JA. Saline-induced hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis. Crit Care Med. 2002 Jan;30(1):259-61.

3. Chowdhury AH, Cox EF, et al. A randomized, controlled, double-blind crossover study on the effects of 2-L infusions of 0.9% saline and plasma-lyte 148 on renal blood flow velocity and renal cortical tissue perfusion in healthy volunteers. Ann Surg. 2012 Jul;256(1):18-24.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: passive leg raise, arterial pressure, pulse pressure variation, volume responsiveness, fluid resuscitation (PubMed Search)

Posted: 9/20/2016 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Pitfalls with PLR

Aneman A, Sondergaard S. Understanding the passive leg raising test. Intensive Care Med. 2016; 42:1493-5.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Intracerebral hemorrhage, intraparenchymal hemorrhage, ICH, IPH, hypertensive emergency, blood pressure, neurocritical care, nicardipine (PubMed Search)

Posted: 8/15/2016 by Daniel Haase, MD

(Updated: 9/6/2016)

Click here to contact Daniel Haase, MD

--Aggressive BP management (SBP <140) in atraumatic intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) does NOT signifcantly improve mortality or disability compared with traditional goal (SBP <180) [1]

--However, a lower goal (SBP <140) has been shown to decrease hematoma size and be safe compared to a higher goal (SBP <180) [2]

The recently published ATACH-2 study investigated aggressive BP control in hypertensive acute atraumatic ICH/IPH (intraparenchymal hemorrhage). [1]

--Control group SBP 140-179 mmHg vs. intervention group SBP 110-139 mmHg with nicardipine infusion (control group actually had SBP 140-150 vs. intervention group SBP 120-130 most of the time).

--Study stopped early for futility. No difference in mortality or modified Rankin.

Previously, INTERACT2 demonstrated that aggressive SBP management (<140) was safe, decreasing hematoma expansion leading to a change in some individuals' practice. [2]

1. Qureshi AI, Palesch YY, et al; ATACH-2 Trial Investigators and the Neurological Emergency Treatment Trials Network. Intensive Blood-Pressure Lowering in Patients with Acute Cerebral Hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2016 Jun 8. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 27276234.

2. Anderson CS, Heeley E, et al; INTERACT2 Investigators. Rapid blood-pressure lowering in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jun 20;368(25):2355-65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214609. Epub 2013 May 29. PubMed PMID: 23713578.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: refractory status epilepticus, ketamine, propofol, siezure, midazolam (PubMed Search)

Posted: 8/30/2016 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Ketamine for RSE?

Legriel S, et al. What's new in refractory status epilepticus? Intensive Care Med 2016. [Epub ahead of print]

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: DKA (PubMed Search)

Posted: 8/23/2016 by Rory Spiegel, MD

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

Is it possible to have a patient present in diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) with both negative serum and urinary ketone levels?

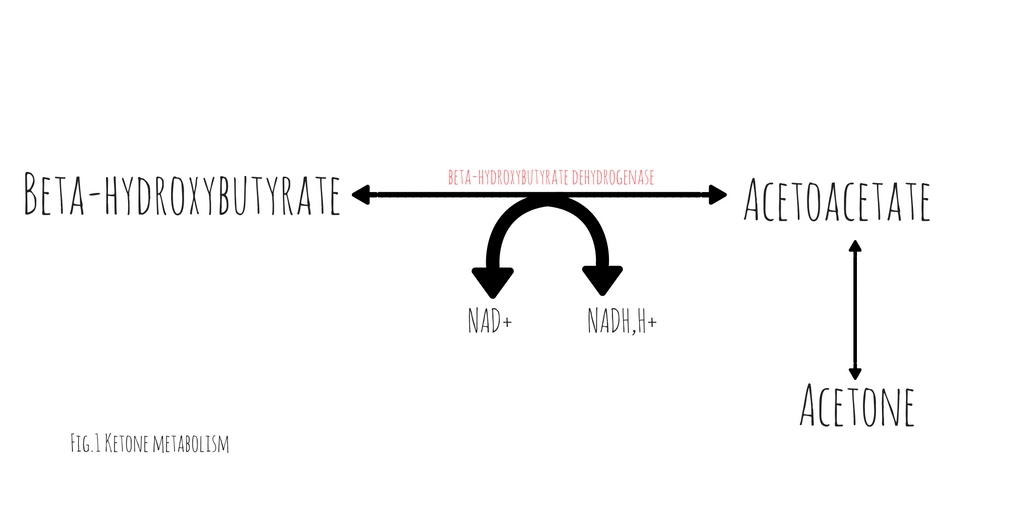

A case report published in American Journal of Emergency Medicine by Jehle et al provides a helpful reminder of this phenomenon (1). The degree of acidosis is directly related to the ratio of the various ketones/ketone metabolites: acetone, acetoacetate and beta-hydroxybutyrate present in the serum. The proportion of each respective substance is determined by the existing redox state in the blood. At any given time, acetoacetate and beta-hydroxybutyrate exist in an equilibrium dependent upon the ratio of NAD+ and NADH(fig.1). These substances freely convert with the assistance of the enzyme beta- hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase (2). This conversion requires the donation of a hydrogen atom from NADH. The balance between beta-hydroxybutyrate and acetoacetate, is determined by the ratio of NADH to NAD+. Acetoacetate will freely degrade into acetone through non-enzymatic decarboxylation. Early in DKA, acetoacetate is the most prevalent substance. As the disease progresses and the serum ratio of NADH to NAD+ increases, the proportion of beta-hydroxybutyrate rises, decreasing the quantity of acetoacetate and acetone.

hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase (2). This conversion requires the donation of a hydrogen atom from NADH. The balance between beta-hydroxybutyrate and acetoacetate, is determined by the ratio of NADH to NAD+. Acetoacetate will freely degrade into acetone through non-enzymatic decarboxylation. Early in DKA, acetoacetate is the most prevalent substance. As the disease progresses and the serum ratio of NADH to NAD+ increases, the proportion of beta-hydroxybutyrate rises, decreasing the quantity of acetoacetate and acetone.

Traditional serum and urinary ketone assays react strongly to acetoacetate but neither reliably react with beta-hydroxybutyrate. Patients in whom the majority of their anion gap is filled by beta-hydroxybutyrate, urinary or serum ketone levels may be negative. In such cases, serum beta-hydroxybutyrate assays would be positive but are not universally available.

It is important to note, with resuscitation and insulin therapy, the ratio of NADH/NAD+ will start to normalize causing an increase in the quantity of acetoacetate. As the patient improves and the anion gap clears, the degree of ketones detected in the serum and urine will paradoxically increase.

1. Jehle D, et al, Severe diabetic ketoacidosis presenting with negative serum ketones: First case report and a review of the mechanism, Am J Emerg Med (2016)

2. Konijn, Abraham M., Naama Carmel, and Nathan A. Kaufmann. The redox state and the concentration of ketone bodies in tissues of rats fed carbohydrate free diets. The Journal of nutrition 10 (1976): 1507.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Zika Virus, Guillain-Barre (PubMed Search)

Posted: 8/9/2016 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Zika Virus-associated GBS

Thiery G, et al. Zika virus-associated Guillain-Barre syndrome: a warning for critical care physicians. Intensive Care Med 2016; epub ahead of print.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: ROSC, Cardiac Arrest, ETCO2 (PubMed Search)

Posted: 8/2/2016 by Rory Spiegel, MD

Click here to contact Rory Spiegel, MD

Despite a lack of prospective data, end-tidal CO2 (ETCO2) is often proposed as a viable replacement for the traditional pulse check to identify return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) in patients presenting to the Emergency Department in Cardiac Arrest. A recent study by Tat et al examined this very question. The authors prospectively enrolled 178 patients suffering out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) and examined the accuracy of a rise in ETCO2 at predicting ROSC. The authors examined both a rise of 10 and 20 mm Hg in ETCO2. Of the 178 patients included in this cohort, 60 (34%) experienced ROSC. The sensitivity and specificity of ETCO2 to predict ROSC at a threshold of 10 mm Hg was 33% and 97% respectively. At a threshold of 20 mm Hg ETCO2 performed no better with a sensitivity and specificity of 20% and 99% respectively.

What this data suggests is while a rise of ETCO2 of greater than 10 is highly suggestive of ROSC, the contrary cannot be said. The absence of a spike in ETCO2 does not rule out ROSC, as the large majority of patients experiencing ROSC in this cohort did so without demonstrating a significant rise in ETCO2. This evidence suggests that ETCO2 is a poor surrogate for a pulse check.

Tat LC, Ming PK, Leung TK, Abrupt rise of end tidal carbon dioxide level was a specific but non sensitive marker of return of spontaneous circulation in patient with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, Resuscitation (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.04.018

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 7/26/2016 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Predicting Fluid Responsiveness with ETCO2

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 7/20/2016 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Bucher J, Koyfman A. Intubation of the neurologically injured patient. J Emerg Med 2016; 49:920-7.

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 7/12/2016 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

LVADs and RV Failure

Sen A, et al. Mechanical circulatory assist devices: a primer for critical care and emergency physicians. Crit Care 2016; 20:153.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Respiratory failure (PubMed Search)

Posted: 6/21/2016 by Feras Khan, MD

Click here to contact Feras Khan, MD

There are 4 types of respiratory failure that all providers should be familiar with

Type 1: Hypoxemic, PaO2 <50; this can include shunt , V/Q mismatch, or high altitude. Pulmonary edema, ARDS, pneumonia are common causes of this type of failure.

Type 2: Hypercapnic respiratory failure; decreased RR or tidal volume. This includes neuromuscular disorders including GBS or Myasthenia Gravis, in addition to medication overdose. COPD and asthma can lead to this type of respiratory failure as well.

Type 3: Peri-operative; atelectasis; decreased FRC from being supine or obese during the operative period.

Type 4: Shock or hypoperfusion leading to increased work of breathing and respiratory failure.

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 6/15/2016 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Heat Stroke

Gaudio FG, Grissom CK. Cooling methods in heat stroke. J Emerg Med 2016; 50:607-16

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: PPI, GI bleed, UGIB, GI hemorrhage (PubMed Search)

Posted: 6/7/2016 by Daniel Haase, MD

Click here to contact Daniel Haase, MD

1. Laine L, Jensen DM. Management of patients with ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 Mar;107(3):345-60; quiz 361. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.480. Epub 2012 Feb 7. Review. PubMed PMID: 22310222.

2. Barkun AN, et al; International Consensus Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Conference Group. International consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2010 Jan 19;152(2):101-13. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00009. PubMed PMID: 20083829.

3. Sachar H, Vaidya K, Laine L. Intermittent vs continuous proton pump inhibitor therapy for high-risk bleeding ulcers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Nov;174(11):1755-62. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4056. Review. PubMed PMID: 25201154; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4415726.

4. Neumann I, et aI. Comparison of different regimens of proton pump inhibitors for acute peptic ulcer bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jun 12;(6):CD007999. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007999.pub2. Review. PubMed PMID: 23760821.

5. Pantoprazole. Micromedex 2.0. Truven Health Analytics, Inc. Available at http://micromedexsoultsions. Accessed June 7, 2016.